| Issue |

J Oral Med Oral Surg

Volume 31, Number 2, 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 10 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2025014 | |

| Published online | 29 April 2025 | |

Original Research Article

A French practice study within the Group for the Study of Oral Mucosa (GEMUB): Allopathic treatment of oral lichen

1

Oral Surgery Department, CHU Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France

2

Université de Bordeaux, Département de chirurgie orale, UFR d'Odontologie, Bordeaux, France

3

INSERM, BIOTIS, U1026, Université de Bordeaux, 33076 Bordeaux, France

* Corresponding author: lelia.menager@hotmail.com

Received:

29

January

2025

Accepted:

12

February

2025

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis of unknown origin, generally affecting the skin, nails and scalp. It can also affect the mucous membranes of the oral cavity and ano-genital region. Due to the paucity of randomised controlled trials, no standardised, universally effective approach to the management of oral lichen has been identified. The main objective of this study was to describe the prescribing of drug therapies for the treatment of OLP. Data were collected by means of a questionnaire sent to members of the Group for the Study of Oral Mucosa (GEMUB). Of the 168 GEMUB members in 2023, 56 completed the questionnaire, giving a response rate of 33.3 per cent. 41 per cent were oral surgeons, 34 per cent dermatologists and 12.5 per cent dental surgeons. The most frequently prescribed first-line treatment (for all clinical forms) was local corticosteroid therapy (100 per cent of responses). The most frequently prescribed second-line treatment was topical tacrolimus (48.2 per cent of responses). As a third-line treatment for isolated oral lichen planus, 25 per cent of questionnaire respondents referred their patients to another specialist. Our results highlight significant variability in treatment choices, underscoring the urgent need for evidence-based clinical guidelines to standardise practices and improve clinical outcomes for patients with this complex pathology.

Key words: oral lichen planus / drug treatments / corticoids / immunosup-pressants

© The authors, 2025

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Lichen planus (LP) is an inflammatory dermatosis of dysimmune origin resulting from cell-mediated immunological dysfunction [1,2]. It is a chronic disease of unknown aetiology that typically affects the skin, nails and scalp [3]. LP can also involve the mucous membranes of the oral cavity, nose, larynx, oesophagus, gastrointestinal tract, conjunctivae and anogenital region [4,5]. Exceptionally, the external auditory canal may also be affected [6,7]. The most frequent sites of lichen involvement are the skin and oral mucosa. In 25 per cent of cases, oral manifestations are the sole clinical feature of the disease [8,9]. The nosology of oral lichen is complex but has recently been clarified in GEMUB's diagnostic management recommendations (Table I). Nevertheless, there are no existing guidelines for the treatment of oral lichen.

Despite numerous publications on the allopathic treatments of oral lichen, there is limited scientific evidence from randomised clinical trials to recommend one treatment over another, apart from topical corticosteroid therapy. Topical corticosteroids are suggested as the first-line treatment, yet their efficacy in relieving pain remains debatable, as does their effect on the clinical progression of lesions [10]. Moreover, unresolved questions persist, such as: which clinical forms of lichen should be treated with topical corticosteroids? For how long? And with what galenic formulation?

In cases of ineffective topical corticosteroid therapy, alternative allopathic treatments are considered [1,11]. Several drug classes and molecules have been proposed: systemic or injectable corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, topical and systemic retinoids, topical or systemic cyclosporine, hydroxychloroquine, oral dapsone, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, methotrexate, thalidomide and certain biologics (anti-TNF agents, JAK inhibitors) [3,12]. Published studies often suffer from limitations such as small sample sizes, heterogeneity in treatment protocols and lack of long-term follow-up.

The absence of best practice recommendations for the treatment of oral lichen, combined with disparate studies and prescriptions from various medical specialties, likely results in significant variability in the medical management of oral lichen. This variability has not yet been described within a population of specialists in France.

The primary objective of this study was to describe medication prescriptions for the treatment of oral lichen among specialists within GEMUB and to identify factors influencing these prescriptions. In the absence of reliable bibliographic data, this "snapshot" could serve as a foundation for developing treatment recommendations for oral lichen.

Different forms of oral lichen.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional observational study using a closed-ended questionnaire distributed to all members of the Group for the Study of Oral Mucosa (GEMUB).

Source population

GEMUB is a scientific society aiming to enhance knowledge, practices and management of oral mucosal diseases through joint efforts in initial and continuing education, the development of diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines, and the establishment of scientific and clinical research projects. GEMUB members are medical professionals specialising in the diagnosis and treatment of oral mucosal diseases, including oral surgeons, dermatologists, stomatologists, otolaryngologists, dentists, maxillofacial surgeons and researchers. The association had 168 members in 2023.

Questionnaire development

The questionnaire consisted of 16 multiple-choice items (Figure 1). The first part focused on first-line treatments, galenic formulations, initial prescription durations and factors influencing prescription choices. The second part addressed second- and third-line treatments. The third part examined long-term prescription practices after disease control and the influence of specialty on management approaches.

|

Figure 1 Questionnaire sent to GEMUB members. |

Data collection

The questionnaire was available online for one year, starting in January 2023, and was distributed via the GEMUB mailing list, the association's usual communication tool.

Results

Out of the 168 GEMUB members in 2023, 56 responded to the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 33.3 per cent. Among respondents, 41 per cent were oral surgeons, 34 per cent dermatologists and 12.5 per cent dentists. Other specialties represented included maxillofacial surgery (8.9 per cent), stomatology (1.8 per cent) and oral medicine (3.5 per cent). Half of the respondents practised in hospital-university settings, 37.5 per cent in hospitals and 28.5 per cent in private practices.

|

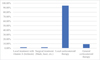

Figure 2 Galenic forms of local corticosteroid therapy are most frequently prescribed as first-line treatment. |

First-line treatment, galenic forms and initial prescription durations

All respondents prescribed topical corticosteroids as the first-line treatment. No practitioners prescribed systemic corticosteroids, topical or systemic retinoids, or topical or systemic immunosuppressants. The most commonly prescribed galenic form for topical corticosteroids was mouthwash (57.1 per cent), followed by compounded formulations with Orabase or other carriers (34 per cent), topical corticosteroid creams (30.4 per cent), and "Buccobet" tablets (5.4 per cent). Corticosteroid sprays and intralesional injections were rarely or never prescribed (Figure 2).

At the initial diagnostic phase, prescription durations varied between one and twelve weeks (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 Most frequent duration of prescription of first-line local corticosteroid therapy. |

Factors influencing first-line prescription choices

Factors influencing treatment choices included pain (78.6 per cent) and clinical form (ulcerative, erythematous, or bullous, whether painful or not) (82.1 per cent). In 7.1 per cent of cases, prescriptions were systematic regardless of pain or clinical form. Neither the risk of progression to squamous cell carcinoma nor histological findings were considered in treatment choices. Nevertheless, the extent of the lichen appeared to influence the decision to prescribe local treatment. Local treatments were prescribed by 83.9 per cent of respondents for localised oral lichen, 64.3 per cent for diffuse oral lichen, and 19.6 per cent for multifocal lichen (oral and other sites).

For keratotic oral lichen without extraoral involvement, asymptomatic with a reticular appearance, the majority of practitioners did not prescribe any treatment (82.1 per cent). Nevertheless, 16.1 per cent prescribed topical corticosteroids, and 7.1 per cent prescribed a vitamin A-based topical treatment (tretinoin). Systemic corticosteroids or local immunosuppressants were never prescribed (Figure 4).

For a non-painful, plaque-like, keratotic oral lichen without extraoral involvement, the majority of respondents prescribed no treatment (71.4 per cent). 14.3 per cent prescribed local corticosteroids, 10.7 per cent recommended local vitamin A treatment (tretinoin), and 14.3 per cent recommended surgical treatment (scalpel, laser, etc.) (Figure 5).

For a non-painful, erythematous, erosive or ulcerative oral lichen without extraoral involvement, 94.6 per cent of the questionnaire respondents prescribed local corticosteroids, and 8.9 per cent prescribed systemic corticosteroids (Figure 6).

|

Figure 4 Most frequently prescribed first-line treatments for painless reticulated forms. |

|

Figure 5 Most frequently prescribed first-line treatments for a non-painful plaque-like keratotic form. |

|

Figure 6 Most frequently prescribed first-line treatments for an erythematous, erosive, or ulcerative clinical form. |

|

Figure 7 Most frequently prescribed second-line treatment. |

|

Figure 8 Most frequently prescribed third-line treatment. |

Second-line treatments

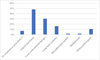

The most frequently prescribed second-line treatment for isolated oral lichen was topical tacrolimus (48.2 per cent). 30.4 per cent prescribed local corticosteroids in another galenic form, 16.1 per cent prescribed long-term systemic corticosteroids, 10.7 per cent prescribed hydroxychloroquine, and 7.4 per cent referred their patients (Figure 7).

Third-line treatments

For isolated LPO/LLO, the third-line treatment most often prescribed by 25 per cent of GEMUB respondents was patient referral. The most frequently prescribed treatment was long-term systemic corticosteroids (19.6 per cent). 16.1 per cent prescribed methotrexate, 14.3 per cent prescribed local corticosteroids in another galenic form, 12.5 per cent prescribed hydroxychloroquine, 10.7 per cent prescribed topical tacrolimus, 8.9 per cent prescribed mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), 7.1 per cent prescribed acitretin, and 3.6 per cent prescribed azathioprine (Figure 8).

Treatment of oral lichen after control of initial manifestations

When oral lichen was controlled (absence of pain but persistent non-suspicious keratosis), 91 per cent of participants prescribed treatment to be taken as needed during a new inflammatory flare, while 30.6 per cent prescribed continuous long-term treatment.

Influence of specialisation on management

95.6 per cent of oral surgeons, 89.5 per cent of dermatologists and 100 per cent of dental surgeons who responded to the questionnaire prescribed topical corticosteroids as first-line treatment for oral lichen without extraoral involvement in an erythematous, erosive or ulcerative form.

43.5 per cent of oral surgeons, 63.1 per cent of dermatologists and 14.3 per cent of dental surgeons prescribed topical tacrolimus as second-line treatment for oral lichen without extraoral involvement.

26.1 per cent of oral surgeons, 21 per cent of dermatologists and 42.8 per cent of dental surgeons prescribed local corticosteroids in another galenic form as second-line treatment for oral lichen without extraoral involvement.

Dermatologists did not refer their patients with oral lichen to another specialist but followed them through the entire treatment.

69.6 per cent of oral surgeons and 85 per cent of dental surgeons referred their patients with oral lichen at some point during treatment.

Among these oral surgeons, 18.75 per cent referred at first-line, 50 per cent referred at second-line, and 31.25 per cent referred at third-line.

Among dental surgeons, 16.6 per cent referred at first-line, 66.6 per cent referred at second-line and 16.6 per cent referred at third-line.

Discussion

This study described the prescription habits of GEMUB members for oral lichen and documented the factors influencing these prescriptions. Our study may include a bias related to the response rate of the questionnaire among GEMUB members. Nevertheless, the response rate of 33.6 per cent is comparable to typical response rate for such surveys, which is around 35 per cent [13]. These results should not be extrapolated to all practitioners managing this pathology, as the studied sample was not intended to represent this population. Nevertheless, it is a multidisciplinary sample and the response rates are generally in line with the representation of the professions within GEMUB. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable information about current practices in prescribing treatments for oral lichen.

Topical corticosteroids were prescribed as first-line treatment by 100 per cent of questionnaire respondents, regardless of profession. This consensus aligns with the literature, where topical corticosteroids are considered the treatment of choice for first-line therapy [7,11]. Nevertheless, the choice of the most frequently prescribed galenic form varied. Mouthwashes were most commonly used in our study, whereas in Spain, the most frequent prescription was 0.1 per cent triamcinolone acetonide ointment applied three times daily [1].

Prescription durations ranged from one to twelve weeks, with higher frequency at one and two months, which is consistent with recommendations from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology [2].

The main factors influencing whether or not to prescribe local first-line treatment were pain and the type of lesions. Keratotic or plaque-like forms were most often not treated, while erythematous, erosive or ulcerative forms received local treatment. This finding is in agreement with numerous publications recommending treatment based on the clinical form of lichen and associated pain [4–6,14–17].

Topical treatments are generally reserved for localised forms. The prescription rate for local treatment decreases with the extent and multifocal nature of lesions. This result aligns with several publications recommending systemic medications when oral lichen is diffuse or affects other mucocutaneous sites [4,18].

The choice of second-line treatment was less homogeneous than first-line treatment. Topical tacrolimus was most commonly prescribed (48.2 per cent of prescriptions), followed by a change in the galenic form of corticosteroids (16.7 per cent). Prescription choice appeared to be influenced by profession. Dermatologists were more likely to prescribe tacrolimus than other specialists. This result aligns with the restriction of tacrolimus prescriptions to dermatologists and paediatricians.

Topical tacrolimus was proposed as a second-line treatment by the majority of respondents. However, this result is not clearly supported by clinical studies, which are contradictory [10,15].

The variability in third-line treatments reflects the lack of studies recommending any specific molecule with certainty. Notebly hydroxychloroquine, which had been recommended by some for second-line treatment, ranks only fourth behind systemic or local corticosteroids in another galenic form and methotrexate. This finding is in agreement with numerous publications showing that corticosteroid therapies (topical vs. systemic) are more frequently prescribed than methotrexate or hydroxychloroquine [10]. This may be explained by the considerable variability in the galenic forms of corticosteroids (topical vs. systemic), which allows treatment to be tailored to the clinical forms of lichen. Hydroxychloroquine has proven effective in other inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus and has been used in 334 patients with oral lichen in 11 studies, four of which were Randomised controlled trials. The dosage was 400 mg/day in two doses. The results showed a reduction in pain and lesions. Its role in the therapeutic arsenal for oral lichen remains to be determined, as there appears to be no consensus [19]. Nevertheless, the safety of use and the relatively large number of patients treated with positive results in four Randomised clinical trials lead us to propose this treatment as first-line systemic therapy ahead of methotrexate, systemic corticosteroids and mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic corticosteroids were used in four clinical studies (including four clinical trials, one of which was a Randomised controlled trial). The dosage was 1 mg/kg of prednisone or prednisolone [14,20–22]. Despite the limited data in this indication, systemic corticosteroids are recommended as second-line treatment and ranked first among third-line treatments. The use of systemic corticosteroids, despite side effects and the lack of clear data for this indication, is likely due to the search for rapid anti-inflammatory action, which is not achieved with other immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive treatments. Clinical study results are more nuanced regarding the efficacy of systemic corticosteroids [14].

Methotrexate was used in 134 patients in four clinical studies, two of which were Randomised. The dosage ranged from 2.5 mg to 15 mg per week. The best efficacy was observed when combined with local corticosteroid therapy [20,23–26].

Mycophenolate mofetil was used in 29 patients in three retrospective studies. In these low-evidence studies, mycophenolate mofetil appears to be effective [26–28].

Acitretin was used in 34 patients in two retrospective studies [26,29]. Combination treatment with local corticosteroids was effective.

Azathioprine was used in 34 patients treated in two studies, including one retrospective cohort study. In these studies, azathioprine was found to be effective [26,29].

All third-line treatments should be evaluated in a comparative manner and considered as second or third-line therapy after topical treatments, which is not the case in most studies. This likely explains the variety of prescriptions in our population.

Another important point concerns the off-label use of treatments. Only betamethasone valerate tablets have an approved indication for local treatment of mucosal and oropharyngeal inflammation [30]. Despite this approval, only 5.5 per cent of respondents in our study used this treatment. Some treatments, like clobetasol cream, are approved for inflammatory skin dermatoses, but the label specifies not to apply it to mucous membranes. Some treatments commonly prescribed, such as tacrolimus ointment, are restricted to dermatologists and paediatricians. The use of oral medications in mouthwashes may be questionable, particularly regarding the cost of treatments like tacrolimus. These points emphasise the need for clear guidelines to support practitioners prescribing treatments for oral lichen.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional observational study conducted among GEMUB members documented the practices of prescribing medications for oral lichen. Our results showed consistency in the prescription of topical corticosteroids as first-line treatment, though the galenic forms and prescription durations varied. Factors influencing prescriptions were related to the profession, type of practice and clinical presentation of the lichen (type of lesion, pain, extent). The lack of homogeneity in second and third-line treatments underscores the need for treatment recommendations for oral lichen. Given the absence of Evidence-Based Medicine, the development of recommendations to standardise and validate practices could be achieved through a Delphi method (expert consensus) within GEMUB.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

No data available.

References

- Piñas L, García-García A, Pérez-Sayáns M, Suárez-Fernández R, Alkhraisat MH, Anitua E. The use of topical corticosteroids in the treatment of oral lichen planus in Spain: a national survey. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2017; 22: e264–e269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannides D, Vakirlis E, Kemeny L, Marinovic B, Massone C, Murphy R, et al. European S1 guidelines on the management of lichen planus: a cooperation of the European Dermatology Forum with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 1403–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Huang MY, Armstrong AW. Janus-kinase inhibitors in dermatology: a review of their use in psoriasis, vitiligo, systemic lupus erythematosus, hidradenitis suppurativa, dermatomyositis, lichen planus, lichen planopilaris, sarcoidosis and graft-versus-host disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2023; 90: 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hashimi I, Schifter M, Lockhart PB, Wray D, Brennan M, Migliorati CA, et al. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 103 Suppl: S25.e1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudier M, Ahmed N, Shirlaw P, Setterfield J, Tappuni A, Black MM, et al. A scoring system for mucosal disease severity with special reference to oral lichen planus. Br J Dermatol 2007; 157: 765–77. [Google Scholar]

- Rotaru D, Chisnoiu R, Picos AM, Picos A, Chisnoiu A. Treatment trends in oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions. Exp Ther Med 2020; 20: 198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassem R, Yarom N, Scope A, Babaev M, Trau H, Pavlotzky F. Treatment of erosive oral lichen planus with local ultraviolet B phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 66: 761–766. [Google Scholar]

- G Gorouhi F, Davari P, Fazel N. Cutaneous and mucosal lichen planus: a comprehensive review of clinical subtypes, risk factors, diagnosis and prognosis. ScientificWorldJournal 2014; 2014: 742826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seintou A, Gaydarov N, Lombardi T, Samson J. Histoire naturelle et transformation maligne du lichen plan buccal. 1ère partie: mise au point. Med Buccale Chir Buccale 2012; 18: 89–107. [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Odi G, Manfredi M, Mercadante V, Murphy R, Carrozzo M. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus: corticosteroid therapies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 2: CD001168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Łukaszewska-Kuska M, Ślebioda Z, Dorocka-Bobkowska B. The effectiveness of topical forms of dexamethasone in the treatment of oral lichen planus: a systematic review. Oral Dis 2022; 28: 2063–2071. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davari P, Hsiao HH, Fazel N. Mucosal lichen planus: an evidence-based treatment update. Am J Clin Dermatol 2014; 15: 181–195. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, Noseworthy T, Beck CA, Dixon E, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015; 15: 32. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone M, Goss E, Carrozzo M, Castellano S, Conrotto D, Broccoletti R, et al. Systemic and topical corticosteroid treatment of oral lichen planus: a comparative study with long-term follow-up. J Oral Pathol Med 2003; 32: 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent SD. Diagnosing and managing oral lichen planus. J Am Dent Assoc 1991; 122: 93–94, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, van der Waal I. Disease scoring systems for oral lichen planus: a critical appraisal. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2015; 20: e199–e204. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E Elsabagh HH, Gaweesh YY, Ghonima JK, Gebril M. A novel comprehensive scoring system for oral lichen planus: a validity, diagnostic accuracy and clinical sensitivity study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2021; 131: 304–311. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Moles MA, Ruiz-Avila I, Rodriguez-Archilla A, Morales-Garcia P, Mesa-Aguado F, Bascones-Martinez A, et al. Treatment of severe erosive gingival lesions by topical application of clobetasol propionate in custom trays. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2003; 95: 688–692. [Google Scholar]

- Tillero R, González-Serrano J, Caponio VCA, Serrano J, Hernández G, López-Pintor RM. Efficacy of antimalarials in oral lichen planus: a systematic review. Oral Dis 2024; 30: 4098–4112. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamal Alsakaan NA, Abd-Elsalam S, Fawzy MM, Elwan NM. Efficacy and safety of oral methotrexate versus oral mini pulse betamethasone therapy in the treatment of lichen planus: a comparative study. J Dermatolog Treat 2022; 33: 3039–3046. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtiar R, Noor SM, Paracha MM. Effectiveness of oral methotrexate therapy versus systemic corticosteroid therapy in treatment of generalised lichen planus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2018; 28: 505–508. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone M, Carrozzo M, Castellano S, Conrotto D, Broccoletti R, Gandolfo S. Systemic corticosteroid therapy of oral vesiculoerosive diseases (OVED). An open trial. Minerva Stomatol 1998; 47: 479–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan P, De D, Handa S, Narang T, Saikia UN. A prospective observational study to compare efficacy of topical triamcinolone acetonide 0.1 per cent oral paste, oral methotrexate and a combination of topical triamcinolone acetonide 0.1 per cent and oral methotrexate in moderate to severe oral lichen planus. Dermatol Ther 2018; 31: 12563. [Google Scholar]

- Pedraça ES, da Silva EL, de Lima TB, Rados PV, Visioli F. Systemic non-steroidal immunomodulators for oral lichen planus treatment: a scoping review. Clin Oral Investig 2023; 27: 7091–7114. [Google Scholar]

- Lajevardi V, Ghodsi SZ, Hallaji Z, Shafiei Z, Aghazadeh N, Akbari Z. Treatment of erosive oral lichen planus with methotrexate. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2016; 14: 286–293. [Google Scholar]

- Myers EL, Hollis AN, Culton DA. Effectiveness and tolerability of systemic therapies in oral lichen planus: a retrospective cohort study. JAAD Int 2024; 15: 136–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wee JS, Shirlaw PJ, Challacombe SJ, Setterfield JF. Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in severe mucocutaneous lichen planus: a retrospective review of 10 patients. Br J Dermatol 2012; 167: 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dalmau J, Puig L, Roé E, Peramiquel L, Campos M, Alomar A. Successful treatment of oral erosive lichen planus with mycophenolate mofetil. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007; 21: 259–260. [Google Scholar]

- Verma KK, Mittal R, Manchanda Y. Azathioprine for the treatment of severe erosive oral and generalized lichen planus. Acta Derm Venereol 2001; 81: 378–379. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radfar L, Wild RC, Suresh L. A comparative treatment study of topical tacrolimus and clobetasol in oral lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008; 105: 187–193. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cite this article as: Ménager L., Galvez P., Catros S., Fénélon M., Fricain, J.-C. 2025. A French practice study within the Group for the Study of Oral Mucosa (GEMUB): Allopathic treatment of oral lichen. J Oral Med Oral Surg. 31, 10: https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2025014 https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2025014

All Tables

All Figures

|

Figure 1 Questionnaire sent to GEMUB members. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 2 Galenic forms of local corticosteroid therapy are most frequently prescribed as first-line treatment. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 3 Most frequent duration of prescription of first-line local corticosteroid therapy. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 4 Most frequently prescribed first-line treatments for painless reticulated forms. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 5 Most frequently prescribed first-line treatments for a non-painful plaque-like keratotic form. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 6 Most frequently prescribed first-line treatments for an erythematous, erosive, or ulcerative clinical form. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 7 Most frequently prescribed second-line treatment. |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 8 Most frequently prescribed third-line treatment. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.