| Issue |

J Oral Med Oral Surg

Volume 31, Number 2, 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 11 | |

| Number of page(s) | 5 | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2025006 | |

| Published online | 27 May 2025 | |

Technical Note

Computer-designed surgical guide for bone lid repositioning after removal of a jaw lesion or deeply impacted tooth: a technical note

1

Department of oral surgery, CHU Bordeaux, 33076 Bordeaux, France

2

UFR des Sciences Odontologiques, Univ. Bordeaux, 33000 Bordeaux, France

3

Centre de compétence des Maladies rares, orales et dentaires, O-RARES. Pôle d'Odontologie et Santé buccale, CHU Bordeaux, 33076 Bordeaux, France

* Correspondence: fribourg.emma@gmail.com

Received:

27

June

2024

Accepted:

24

January

2025

Introduction

Minimally invasive surgery still remains a challenge for oral surgeons when considering the removal of a jaw bone lesion or deeply impacted teeth. Conventional surgery using osteotomy can result in significant bone loss and lack of accuracy. The Bone Lid Technique, which was first described in implantology to perform lateral sinus lift procedure, can be applied to the removal of maxillary bone lesions [1]. It consists of creating a bone lid or window using thin osteotomy instruments. The bone lid is removed to access the surgical site and preserved before being returned to its original position with osteosynthesis screws [2]. We hypothesized that the use a surgical cutting guide to perform a bone lid would result in a safer and more accurate procedure. Few studies have reported the use of surgical guides for the removal of jaw bone lesions [3,4]. These studies describe either the use of a drilling locating guide, which allows to perform an initial osteotomy to locate the lesion, or a cutting guide, to define the osteotomy lines. To our knowledge, only few studies have reported the use of a surgical cutting guide to excise bone lesion and none have mentioned bone lid repositioning [3,5].

The aim of this technical note is to describe the protocol and execution of the bone lid technique for lesion or tooth removal, using a 3D surgical cutting guide, illustrated by 2 cases.

Innovation report

The bone lid technique involves creating and temporarily removing a bone segment to access underlying structures, which is then repositioned to preserve bone integrity and promote healing.

Patient 1

A 53-year-old female experienced chronic pain in the right mandible at the site of tooth #37, extracted four months prior. CBCT imaging revealed a mixed radiopaque and radiolucent lesion near the extraction site, adjacent to the inferior alveolar nerve (IAN). To precisely locate and orient the osteotomy while preserving the buccal bone and protecting the IAN, a surgical guide was employed. An optical impression of the mandible was taken using the 3Shape Trios® camera. Planning software (coDiagnostiX, Straumann®) facilitated the integration of STL data from the optical impression with DICOM data from the CBCT. Four markers defined the bone lid's edges, ensuring optimal instrument angulation (Fig. 1). A resin surgical guide was fabricated using a Rapid Shape 3D printer P40 system (Straumann®) (Fig. 2).

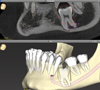

Under local anesthesia, a sulcular incision from teeth #43 to #46, with two releasing incisions between teeth #42 and #43, allowed for a full-thickness flap with adequate flexibility for guide placement (Fig. 3A). The mental foramen was identified and safeguarded throughout the procedure. With the guide in position, a Lindemann burr under irrigation outlined the rectangular bone lid, which was then created using a diamond disc (Frios MicroSaw, Dentsply Sirona Implants®) (Fig. 3B). Bone chisels and a mallet separated the lid, preserved in saline (Fig. 3C). The lesion was curetted and sent for pathological analysis to confirm a cemento-osseous lesion. After rinsing the site with betadine and saline, the bone lid was repositioned and secured with a 1.2 mm × 11 mm osteosynthesis screw (Tekka Global D®) (Fig. 3D). The mucosa was sutured without tension using Vicryl 4.0. The patient exhibited good healing without signs of infection or inflammation.

|

Fig. 1 Guide design on CodiagnostiX Straumann (in white) with 5 different views : axial, transverse and tangential views, 3D reconstruction and 2D panoramic curve reconstruction. We can see the bilateral inferior alveolar nerves (pink), dental implants used to determine the dimensions for the bone's window (yellow). |

|

Fig. 2 Surgical printed guide. |

|

Fig. 3 Surgical procedure in patient 1. (A) Positioning of the surgical guide to ensure its proper placement through the dental embrasures; (B) Delineation of the bone lid with a diamond disc; (C) Removal of the bone lid prior to lesion resection; (D) Fixation of the bone lid with a single microscrew. |

Patient 2

An 11-year-old boy required extraction of an impacted tooth #36. CBCT imaging showed the tooth deeply impacted between teeth #35 and #37, with the IAN in close proximity and a thick buccal wall without bone fenestration. To minimize bone damage and protect the IAN, the bone lid technique with a surgical guide was chosen. A mandibular optical impression was obtained, and coDiagnostiX® software merged the STL and DICOM data (Fig. 4). The bone lid was designed to avoid damage to adjacent teeth, and a resin surgical guide was produced using the Rapid Shape 3D printer P40 system (Straumann®) (Fig. 5).

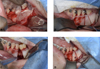

The procedure, performed under local anesthesia, involved a sulcular incision from teeth #33 to #37, with two releasing incisions on the right mandibular ramus and between teeth #33 and #34, allowing for a full-thickness flap with sufficient flexibility for guide placement (Fig. 6A). The mental foramen was identified, and the IAN was protected throughout the surgery. With the guide in place, a Lindemann burr under irrigation defined the rectangular bone lid, created using piezosurgery (Piezotome, Acteon®) (Fig. 6B). Bone chisels and a mallet separated the lid, preserved in saline (Fig. 6C). Following corono-radicular separation, the tooth was extracted, and the site irrigated with betadine and saline. The bone lid was repositioned and fixed with a 1.2 mm × 13 mm osteosynthesis screw (Tekka Global D®) (Fig. 6D). The mucosa was sutured without tension using Vicryl 4.0. The patient demonstrated good healing without infection, inflammation, or neuropathic complications.

|

Fig. 4 Guide design on CodiagnostiX Straumann. |

|

Fig. 5 Surgical printed guide. |

|

Fig. 6 Surgical procedure in patient 2. (A) Positioning of the surgical guide to ensure its proper placement through the dental embrasures; (B) Delineation of the bone lid using piezosurgery; (C) Removal of the bone lid prior to tooth extraction; (D) Fixation of the bone lid with a single microscrew. |

Discussion

Guided surgery is extensively used in oral and maxillofacial surgeries, particularly in implantology, orthognathic surgery and oncology. The use of computer-designed surgical guides to remove benign jaw bone lesions or to extract deeply impacted teeth is less common [3]. The bone lid technique offers a bone-preserving alternative to conventional ostectomy. This method involves creating and temporarily removing a bone segment to access the surgical site, which is then repositioned to maintain bone integrity [2]. Advancements in instruments, such as microsaws and piezosurgery, have enhanced the precision of osteotomies, facilitating accurate repositioning and stabilization of the bone lid with minimal hardware.

In our cases, we employed computer-designed surgical guides to delineate the bone lid boundaries accurately. These guides enable precise osteotomy placement, thereby safeguarding adjacent anatomical structures and ensuring accurate lesion localization, especially in edentulous regions lacking clear landmarks. We opted for tooth-supported guides with windows on select teeth to verify correct intraoperative positioning [3]. While bone-fixed guides are an alternative, they necessitate more extensive mucosal flaps.

Literature supports the efficacy of using cutting guides in conjunction with the bone lid technique. For instance, a study involving 10 patients demonstrated favorable bone healing at six months postoperatively when using cutting guides and bone lid repositioning [6]. Another study compared guided versus freehand surgery for maxillary odontoma removal in 10 patients, concluding that guides significantly improved precision, reduced invasiveness, and decreased operative time and patient discomfort [3]. However, the requirement for larger mucosal flaps with guided surgery should be considered. Thus, bone preservation is much improved with this technique, which is associated with less post-operative pain for the patient [7]. Another study used a localization guide to make the osteotomy as close as possible to the impacted teeth to be extracted in 40 patients [8]. It demonstrated the importance of precise lesion localization and excision, especially in the vicinity of anatomical structures such as the inferior alveolar nerve, maxillary sinus and adjacent teeth.

A comprehensive review by Sivolella et al. analyzed 139 bone flaps across four studies, focusing on the bone lid technique for accessing mandibular cysts and impacted teeth [2]. Notably, only one study reported the use of a surgical guide to define the bone flap margins, possibly due to the associated costs [9]. Investing in in-house three-dimensional printing technology could mitigate these expenses.

Conclusion

This technical note underscores the advantages of integrating 3D printing technologies with the bone lid technique for the removal of mandibular bone lesions and deeply impacted teeth. The synergy of these approaches enhances surgical precision and safety while reducing invasiveness and operative duration. Further research is warranted to validate the benefits of surgical cutting guides in repositioning bone windows post-extraction of deeply impacted teeth or benign jawbone lesions.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare the absence of conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Fribourg Emma, upon reasonable request.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or families.

References

- Teixeira KN, Sakurada MA, Philippi AG, Gonçalves TMSV. Use of a stackable surgical guide to improve the accuracy of the lateral wall approach for sinus grafting in the presence of a sinus septum. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;50:1383–1385. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivolella S, Brunello G, Panda S, Schiavon L, Khoury F, Del Fabbro M. The bone lid technique in oral and maxillofacial surgery: a scoping review. J Clin Med 2022;11:3667. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gernandt S, Tomasella O, Scolozzi P, Fenelon M. Contribution of 3D printing for the surgical management of jaws cysts and benign tumors: a systematic review of the literature. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2023;124:101433. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Choi S, Chae YK, Jung J, Choi SC, Nam OH. Customized surgical guide with a bite block and retraction arm for a deeply impacted odontoma; a technical note. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021;122:456–457. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ketele A, Meeus J, Shaheen E, Verstraete L, Politis C. The usefulness of cutting guides for resection or biopsy of mandibular lesions: a technical note and case report. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg 2023;124:101272. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Lai Q, Xue R, Ci J. Hard tissue preservation and recovery in minimally invasive alveolar surgery using three-dimensional printing guide plate. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33:e476–e481. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YK, Xie QY, Yang C, Xu GZ. Computer-designed surgical guide template compared with free-hand operation for mesiodens extraction in premaxilla using “trapdoor” method. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7310. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Wang X, Shan P, Hu S, Liu D, Ma J, Nie X. A randomized controlled trial: evaluation of efficiency and safety of a novel surgical guide in the extraction of deeply impacted supernumerary teeth in the anterior maxilla. Ann Transl Med 2022;10:292. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelazez AKH, Hany HE, El Din MEG, El Meregy MMM, Abdelhameed AMF, El-Kabany IM, Abdelraouf AM, Salah M, El Hadidi YN, El Abdien MDZ. The evaluation of the effect of performing guided lid surgery with enucleation of a cystic lesion; a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2022;97:107385. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cite this article as: Fribourg E, Catros S, Fricain J-C, Fenelon M. 2025. Computer-designed surgical guide for bone lid repositioning after removal of a jaw lesion or deeply impacted tooth: a technical note. J Oral Med Oral Surg. 31, 11: https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2025006

© The authors, 2025

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Guide design on CodiagnostiX Straumann (in white) with 5 different views : axial, transverse and tangential views, 3D reconstruction and 2D panoramic curve reconstruction. We can see the bilateral inferior alveolar nerves (pink), dental implants used to determine the dimensions for the bone's window (yellow). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Surgical printed guide. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Surgical procedure in patient 1. (A) Positioning of the surgical guide to ensure its proper placement through the dental embrasures; (B) Delineation of the bone lid with a diamond disc; (C) Removal of the bone lid prior to lesion resection; (D) Fixation of the bone lid with a single microscrew. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Guide design on CodiagnostiX Straumann. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Surgical printed guide. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Surgical procedure in patient 2. (A) Positioning of the surgical guide to ensure its proper placement through the dental embrasures; (B) Delineation of the bone lid using piezosurgery; (C) Removal of the bone lid prior to tooth extraction; (D) Fixation of the bone lid with a single microscrew. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.