| Issue |

J Oral Med Oral Surg

Volume 25, Number 2, 2019

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 13 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | Article original / Original article | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2018041 | |

| Published online | 08 March 2019 | |

Original Article

Pilot study in France about the infiltration of local anaesthetics associated to oral surgery procedures performed under general anaesthesia

1

UFR Odontology and Oral Surgery Department, Reims, France

2

UFR Odontology and Public Health Department, Reims, France

* Corresponding author: charlottedeverbizier@hotmail.fr

Received:

11

October

2018

Accepted:

24

December

2018

Introduction: Opinions differ regarding the combined use of local anaesthesia (LA) and general anaesthesia (GA) in oral surgery procedures. The aim of this study was to evaluate practices in France concerning intraoperative LA for oral surgery performed under GA. Practitioners and method: We conducted a prospective survey of 250 oral surgery practitioners (CNIL-2045135v0 e) and carried out a literature review with the MEDLINE search engine (PubMed) covering the period from January 2000 to September 2017. Results: Among the 77 practitioners who participated, 88.3% were dental practitioners, the majority of whom were in the 25–34-yr age group. More than half (59%) infiltrated the surgical site; 46% pre-operatively, 24% intraoperatively and 11% post-operatively. Discussion: LA under GA appears to have advantages for post-operative pain management, dissection of the first mucosal plane and bleeding management pre- and post-operatively. The contraindications remain the same as for patients in a vigilant state. In children, it should be used in moderation to limit the risk of self-inflicted lip or mouth trauma during recovery. Conclusion: The indications of LA under GA are operator-dependent and the analysis of the literature did not allow us to determine the interest or not of LA administered intraoperatively during oral surgery performed under GA.

Key words: local anaesthesia / general anaesthesia / oral surgery

© The authors, 2019

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

A surgical procedure is a medical procedure that involves extracting a structure or reaching a target organ after incision on an anesthetized patient. Throughout the world, in 2008, approximately 234 million surgical procedures were performed [1]. Dental extractions are the most commonly performed operations, e.g., ten million third molars are extracted in the United States each year [2]. If a large number of oral surgeries are performed under local anaesthesia (LA), other interventions of this type can be performed under general anaesthesia (GA). In this case, the anaesthesiologist induces a loss of consciousness by acting on subcortical and cortical circuits through the administration of hypnotics [3]. Sometimes he induces muscular relaxation with the help of curare derivatives. The anaesthesiologist also manages the pain of the patient pre- and post-operatively with opioids and analgesics. During certain surgeries carried out under GA, LA products such as articaine or lidocaine with or without vasoconstrictors can also be used. For oral surgery procedures performed under GA (wisdom tooth extraction, enucleation of cystic lesions, apical resections or supernumerary tooth extraction...), infiltration of the operative site is sometimes performed by surgeons. LA is normally used to stop reversible nerve conduction in order to raise the threshold of pain. The duration of LA action varies depending on the molecule and the dose used, the area being anaesthetized and the associated vasoconstrictor molecules. LA vasoconstrictor solutions are used in oral surgery to reduce dispersion of LA in the vascular system which in turn reduces their systemic toxicity and prolongs their action. The vasoconstrictor can contribute to the surgeon's comfort during surgery by locally decreasing the bleeding [4], thus facilitating the surgical procedure and reducing its duration. Thus, the reasons given to justify the addition of LA are the following: increased operative comfort by the ensuing reduction of bleeding in the operative site, easier handling in soft tissue distension [5], and reduced pain for patients post-operatively. This practice also permits lower systemic additions of analgesic products pre- and post-operatively [4,6]. Those who are opposed to this practice argue that the use of LA products only increases the operating time, increases the probability of a toxic and/or allergic incident, and may alter the heart rate during the procedure. In addition, LA causes numbness, which can increase the risk of bite injuries during recovery. Finally, it is not felt to be necessary because analgesics are sufficient to counter post-operative pain [6]. In fact, opinions diverge on the interest of combining LA with GA in pre- and post-operative procedures especially regarding the management of the pain, the reduction in the quantity of drugs administered by the anaesthesiologist during the operation and even the management of post-operative haemostasis [7]. In this context, the aim of this work is to evaluate the practices in France concerning LA administered intraoperatively for oral surgery performed under GA and to complete this evaluation by a review of the literature.

Practitioners and methods

Design

This was a survey of about 250 practitioners performing oral surgery under GA. It was conducted between June 17, 2017 and August 28, 2017, using an electronic questionnaire sent by email (google docs © software). The study was completed by a narrative review of selected articles in PubMed.

Ethics

The project was approved by the National Informatics and Liberty Commission (number 2045135 on March 22, 2017). It is non-interventional research involving the human person according to the reference methodology. This study is not subject to the obligation of the Law Jardé no 2012-300, dated March 5, 2012 (decree No. 2017-884, dated May 9, 2017). The approval of an Ethics Committee is not required.

Construction of the questionnaire and validation

A steering committee composed of a public health odontologist, an anaesthesiologist and an oral surgeon developed a set of questions to carry out data collection with the least bias possible. A series of closed multiple-choice questions was formulated, as well as open-ended questions allowing respondents to freely express themselves. Prior to the completion of the survey, a feasibility study was conducted to ascertain whether some questions were difficult to understand and if additional questions needed to be added. This stage of the study was also intended to test the practicality of the Google Docs © software.

Data collection

We obtained the e-mail addresses of 250 oral surgeons and stomatologists practicing in the public or private sectors from databases of the French Society of Oral Surgery. This request was made during the French Society of Oral Surgery congress 2017 at Rouen. For reasons of time and cost, we limited our survey to this available database. Our questionnaire was submitted anonymously by e-mail to all these practitioners. It was sent out over a 3-week period of time.

Data analysis

Categorical variables are presented as percentages and the data were processed with SPSS for Windows version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The response rate was defined as the ratio of the number of interviews conducted to the number of selected eligible individuals, according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR).

Strategy of the documentary research

A bibliographic search was conducted on the MEDLINE database (PubMed) covering the period of January 2000 to September 2017 with no language restrictions. The following MESH words were queried: LA, GA, nerve block. With these words, 825 references were obtained. We searched for the terms “oral surgery, otorhinolaryngological surgery, dental surgery or maxillofacial surgery” in titles and abstracts. A second bibliographic search on Medline with the same method found two additional articles from the journal Oral Medicine and Oral Surgery, and one more from Science Direct. The identified studies were first sorted by title and abstract, we only included studies that explore the effects of LA under GA in oral sphere operations. Nine articles were selected. Two independent reviewers read the abstracts and included articles in the final selection based on their content. In the event of disagreement, the opinion of a third reviewer made it possible to decide on the selection.

Results

Construction of the questionnaire

On the basis of the clinical experience of the members of the steering committee, a first questionnaire consisting of an open question and nine closed questions was developed. This questionnaire, together with an acceptability questionnaire, was sent electronically (google docs © software), to 11 oral surgeons and to an anaesthesiologist who frequently works in stomatology. All the questions were perfectly understood except one concerning “the knowledge of the role of the anaesthesiologist”. Two suggestions were made to add a question about the use of vasoconstrictors and to add prilocaine to the choice of LAs. An additional indication for LA was suggested by two people “the detachment of the mucosal foreground facilitated by infiltration”. The final questionnaire resulting from the feasibility study is presented in the Appendix. It is composed of an open question, six closed questions and four mixed questions.

Sociodemographic data

Out of the 250 questionnaires sent, 77 answers were obtained, representing a response rate of 30.8%. Out of the 77 respondents, the 25–34-yr age group was the most represented (Fig. 1) 88.3% came from the odontology training (Fig. 2).

|

Fig. 1 Age of surgeons. |

|

Fig. 2 Surgical training. |

Current practice

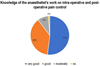

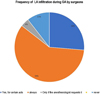

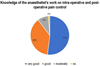

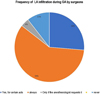

No correlation could be found with SSPS software, so the results are only specified in descriptive form. Half of the practitioners (52%) said that they had specific knowledge of how pain is managed by the anaesthesiologist pre- and post-operatively (Fig. 3). More than half (59%) infiltrate the operative site during procedures performed under GA (Fig. 4); 46% of them pre-operatively, 24% intraoperatively and 11% post-operatively. The reasons why practitioners do not infiltrate LA during a GA are shown in Figure 5.

Practitioners justified the use of LA during a GA as follows: for 59% of them it was for better pain management, 51% stated that it was used to manage bleeding more easily pre- and post-operatively and 28% said they used it to promote tissue detachment. In this case, 36% also used a vasoconstrictor associated with LA, 27% sometimes used it and 6% never associated vasoconstrictors with LA. The frequency of LA depended on the procedure being performed. They are shown in Figure 6.

|

Fig. 3 Knowledge of the anaesthetist's work on intraoperative and post-operative pain control. |

|

Fig. 4 Frequency of local anesthesia (LA) infiltration during general anesthesia (GA) by surgeons. |

|

Fig. 5 Reasons why practitioners do not infiltrate local anesthesia (LA) during a general anesthesia (GA). |

|

Fig. 6 Frequency of local anesthesia (LA) infiltration in relation to the type of act performed under general anesthesia (GA). |

Results of the literature review (Tab. I)

At the end of our selection procedure, nine articles were selected. Literature is sparse on the subject and selected articles provide a low level of proof. The results of our review of the literature are presented in Table I. Three articles show that a combination LA/GA allows a stabilization of vital signs and a decrease in the depth of GA [7–9]. The reduction of analgesic/hypnotic dosages facilitates recovery. The GA/LA association could also be used in order to reduce post-operative pain [10]. Two studies stress the risk of biting anesthetized lips during recovery [6,9]. Other authors mention the advantage of vasoconstrictors for a better post-operative management of haemostasis, but this advantage is debatable considering the stress generated by the presence of LA during recovery, especially in children [7]. Two articles study the contribution of a bilateral lower alveolar block before mandibular sagittal osteotomies [11,12]. They suggest that there is a reduction of post-operative pain when the nerve block is performed. One clinical case reports that a too rapid injection of LA with concentrated vasoconstrictors (1/100 000 adrenaline) could cause severe bradycardia [13].

Summary of the literature review.

Discussion

On a formal level, our study permitted us to verify the usefulness of online questionnaires, with quick response times, easy dissemination of the survey at a modest cost. Adjustments made after the feasibility study improved the relevance of our questionnaire and therefore the interest in this study. The response time to this questionnaire averaged less than 1 min and that was probably an asset in maximizing the number of participants. The results of this survey show that more than one out of two practitioners have diverging opinions on the topic of the LA/GA combination. Moreover, one out of two (48%) practitioners states that they do not have precise knowledge of pain management by the anaesthesiologist pre- and post-operatively. This study shows that the practice of LA pre- or post-operatively is operator dependent. The justification of one practice more than another seems to be based on empirical arguments and the lack of published research proves that the subject has not been explored enough to objectively argue the question.

Nociception is the process by which intense thermal, mechanical or chemical stimuli are detected by a subpopulation of peripheral nerve fibres, called nociceptors. Primary afferent nociceptors convey noxious information to projection neurons within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord [14].This is the painful afferent pathway passing through myelinated afferences, Aδ fibres for acute pain, and through non-myelinated “C” fibres for slow pain [14]. The analgesic molecules of LA and GA counter this painful pathway. For example, during abdominal aortic surgery, it is possible to combine the GA with an epidural anaesthesia [15]. A GA and LA epidural combination with bupivacaine significantly reduces cortisol production. This suggests that LA, in addition to GA, would reduce the patient's stress response during a major operation, thus promoting better management of pre- and post-operative risks [15]. By reducing the endocrine and metabolic response, complication rates are decreased. Similarly, during arthroscopic knee surgery, it is possible to combine LA and GA. An intra-articular injection of LA (most commonly bupivacaine) decreases post-operative pain, reducing and delaying the use of analgesics after surgery. This facilitates early mobilization post-operatively [16]. In Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, the pre-operative infiltration of a solution of bupivacaine during tonsillectomies has wide consensus. This has the effect of reducing post-operative pain by blocking the excitation of nociceptive C fibres during the operation, making it possible to limit the production of algogenic substances [9,17].

Generally, nerve growth factor (NGF) regulates nociceptive functions. During inflammation, it stimulates the nociceptive neurons of the sensitive dorsal root ganglion. This causes hyperalgesia. Ropivacaine acts on NGF, which is then overregulated in the dorsal root of the lymph node and allows inhibition of microglia (the therapeutic target for the treatment of neuropathic pain). This results in a blockage of the afferent actions of the dorsal root of the lymph node, which could potentially prevent the appearance of neuropathic pain. Thus, a peripheral nerve block with the infiltration of 200 mg of bupivacaine prevents the afferent activity specific to the dorsal root of the lymph nodes from occurring, which in turn inhibits the nociceptive pathway and prevents neuropathic pain [18]. In our survey, 35% of practitioners infiltrate after the incision; this seems less efficient in preventing the activation of painful pathways.

Chigurupati et al. [19] found that there may be fluctuations in a patient's vital signs during an operation stimulating the trigeminal nerve when performed under GA. These fluctuations are the result of the trigeminocardiac reflex − a neuroprotective mechanism which can have harmful consequences, such as a sudden decrease in pulse rate with or without a decrease in blood pressure, leading in turn to asystole or even cardiac arrest [19]. They described a case of the dissection of the trigeminal nerve for the management of decompression, where nerve manipulation caused sudden and deep bradycardia (30 beats/min) and hypotension (60/40 mmHg). The anaesthesiologist managed the incident with atropine to regulate these phenomena temporarily but as soon as the surgeon resumed the operation similar changes returned. Finally, the application of a lidocaine impregnated gauze at 1/200 000 on the nerve for 3 min allowed the surgery to continue without further serious hemodynamic changes [19]. The use of a peripheral nerve block seems to significantly reduce the reflex during splitting and mandibular manipulations [20,21]. The depth of GA, which can be represented by the brain index rate, also has a role in the prevention of the trigeminocardiac reflex. The lighter it is, with the use of associated atropine, the higher the frequency of the reflex. The risk of asystole is 4.5 times higher when the trigeminocardiac reflex occurs under mild anaesthesia (cerebral index rate greater than 60). It is then recommended to limit or even stop nerve manipulation, or to infiltrate adrenaline, which can be provided through an LA [22].

For children upon awakening [6] the persistence of oral and/or perioral anaesthesia appears to be a source of stress. In this case, there are arguments in favour of the use of intraoperative opioids, such as morphine sulphate, with or without non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Post-operative nausea and vomiting are two of the most common side effects to occur during the first 24 h post-operatively when GA and morphine are combined. They affect 20–30% of patients. To counter these adverse effects, anti-emetics are prescribed [23] and it has been noted that the use of a lower alveolar nerve block in sagittal osteotomies of the mandible reduces post-operative pain and the frequency of post-operative nausea and vomiting. Ropivacaine is preferred for its long-lasting action both before and after surgery. It would seem, therefore, that infiltration can be effective for a better management of post-operative pain and nausea and vomiting [12].

The quality of intraoperative analgesia would appear to be identical with lidocaine and bupivacaine [24]. Infiltration of LA acts in the early post-operative hours [25]. Bupivacaine seems to provide better post-operative analgesia compared to lidocaine during the first 8 h after surgery. The injection of lidocaine adrenaline provides better analgesia during the first hour post-operatively than the same injected non-adrenaline because its effect is not very long lasting. Two hours after surgery the pain scores increase in the lidocaine adrenaline group, while those in the lidocaine group alone remain stable [26]. The criteria for choosing LA associated pre- or intraoperatively with GA still need to be specified according to the nature of the act to be performed. The use of LA in addition to GA remains controversial, particularly regarding the value of post-operative pain management [6,26].

The combination of LA with vasoconstrictors helps to limit bleeding in the surgical site and thus promotes operator comfort by improving visibility [7,11]. The combination of a vasoconstrictor with the anaesthetic solution reduces the blood dispersion of adrenaline. A decrease in pain through the use of a mandibular block reduces blood pressure by about 10–12%, resulting in lower blood flow and a drier surgical site. This phenomenon could be explained by the decrease in sympathetic tone under LA [11]. The vasoconstriction of blood vessels decreases with the duration of the action of the LA and its associated vasoconstrictor. In cases where intraoperative haemostasis has been neglected, bleeding from the operated site may be observed following secondary vasodilation of the blood vessels, related to LA resorption and post-operative oedema expression [27]. While 51% of practitioners justify LA for better intraoperative bleeding management, only 36% of all practitioners surveyed use vasoconstrictors systematically. Fifty-eight percent infiltrate for the avulsions of wisdom teeth whereas only 33% do it for apical resections. This is surprizing considering that the last surgery requires a filling of the decapitated apex and should be performed under the driest conditions possible in order to assure the visibility of the channels to be blocked.

It is assumed that infiltration detaches the first mucosal plane and thus facilitates the manipulation of the soft tissues. This effect is purely mechanical and is the result of the infiltration of a liquid between the bone and the mucosa [5]. The surgeon can thus more quickly create a flap whether it is of total or partial thickness, and even if the infiltration takes time, this time can be made up for during the overall surgical procedure. Twenty-eight percent of practitioners say they infiltrate because of this facilitated detachment effect. LA is rarely contraindicated; a proven allergy is the first contraindication but allergic accidents remain extremely rare. In a study of 1240 patients, only 0.2% of allergic shocks could be attributed to LA [28]. It is principally contraindicated to administer vasoconstrictors to patients with pheochromocytomas [4]. Vasoconstrictors are banned at least 24 h after cocaine use to eliminate the drug and its active metabolites. Relative contraindications exist to avoid bone necrosis in patients where vascular networks are diminished. Thus, in patients with even less vascularized bone (bone irradiated from 40 Grays or more), vasoconstrictor molecules should be used in moderation. In case of biphosphonate osteonecrosis, the use of vasoconstrictors in LA does not necessarily have to be a concern because it is the result of an abnormal bone turnover and not a loss of vascularity [29].

A first limitation of this study is related to coverage error, which is the main problem of web surveys. Even if the access to and use of the Internet continue to improve, representativeness problems arise. The sociodemographic characteristics of the Internet audience, even if the phenomenon has tended to decrease, are still very marked. For example, in this survey, the 25–34-yr age group is the most represented. A second limitation is due to the size of the panel (77 participants) which does not allow us to statistically highlight the significance of some practices according to the practitioners' medical or dental curriculum, to their place of training, or even their age. With a response rate of only 30.8%, the non-response rate, if it is related to the variables of interest of the respondents, generates a non-response bias in our study [30]. In addition, the short survey completion period (72 days) can account in part for the low response rate. Finally, we did not explore the role of alveolar nerve block in our questionnaire. We should take this point into consideration in a future study.

Conclusion

This investigation has highlighted that infiltration of LA pre-operatively or intraoperatively for oral surgery performed in France under GA is operator dependent. In our study, 59% of practitioners justified it firstly for pain management, haemostasis and then for facilitated tissue dissection. A review of the literature confirms the interest of LA under GA for the management of post-operative pain, soft tissue manipulation and management of bleeding pre- and post-operatively. These preliminary results should be confirmed with a larger population in France and abroad.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ann Pochard for her help with English language correction, and are grateful to the French Society of Oral Surgery for the support given to the study.

Appendix

Document 1: Questionnaire

Local anaesthesia (LA) in oral surgery under general anaesthesia (GA)

This questionnaire is intended for all practitioners performing oral surgeries under general anaesthesia. With the aim of better knowing the protocols of each and to be able to make a summary on the current practices in France.

(1) How old are you?

-

Between 25 and 34 yr

-

Between 35 and 44 yr

-

Between 45 and 55 yr

-

+55 yr

(2) In which city did you study?

(3) What branch did you come from?

-

Odontology

-

Medicine

(4) Do you know how the anaesthesiologist manages pain, both intraoperatively and post-operatively?

-

Very good

-

Good

-

Moderately

-

No

(5) Do you use LA infiltration while performing GA surgery?

-

Yes, for certain acts

-

Yes, for all acts

-

Only if the anaesthesiologist asks you to

-

Never

(6) If yes, for which type(s) of intervention(s)?

-

Wisdom tooth avulsion

-

Multiple dental avulsions

-

Cyst removal

-

Apical resection

-

Other

(7) For what purpose(s)?

-

Pain management

-

Haemostatic quality

-

To promote tissue detachment

-

Other

(8) What molecule(s) do you use during LA under GA?

-

Articaine, Articaïne®

-

Lidocaine, Xylocaïne®

-

Ropivacaine, Naropéïne®

-

Mépivacaïne, Carbocaïne®

-

Other

(9) In the anaesthetic solution you inject, are there any vasoconstrictors?

-

Always

-

Not always

-

Never

(10) When do you inject your LA during GA surgery?

-

Pre-operatively

-

Intraoperatively

-

Post-operatively

(11) If not, why don't you inject an LA during oral surgery under GA?

-

No interest

-

Increases operating time

-

Risks of bite

-

Numbness discomfort

-

Toxic/allergic risk

-

Other

References

- Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A Surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 2009;360:491–499. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JW. The prophylactic extraction of third molars: a public health hazard. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1554–1559. [Google Scholar]

- Akeju O, Brown EN. Neural oscillations demonstrate that general anesthesia and sedative states are neurophysiologically distinct from sleep. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2017;44:178–185. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrid C, Courtois B, Vironneau M, et al. Emploi des vasoconstricteurs en odonto-stomatologie. Med Buccale Chir Buccale 2003;9:65–94. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Richard C, Pascal J, Martin C. Anesthésie locale et régionale en oto-rhino-laryngologie. EMC − Oto-Rhino-Laryngol 2011;6:1–16. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend JA, Ganzberg S, Thikkurissy S. The effect of local anesthetic on quality of recovery characteristics following dental rehabilitation under general anesthesia in children. Anesth Prog 2009;56:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bahlani S, Sherriff A, Crawford PJ. Tooth extraction, bleeding and pain control. J R Coll Surg Edinb 2001;46:261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend JA, Hagan JL, Smiley M. Use of local anesthesia during dental rehabilitation with general anesthesia: a survey of dentist anesthesiologists. Anesth Prog 2014;61:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Watts AK, Thikkurissy S, Smiley M, McTigue DJ, Smith T. Local anesthesia affects physiologic parameters and reduces anesthesiologist intervention in children undergoing general anesthesia for dental rehabilitation. Pediatr Dent 2009;31:414–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginström R, Silvola J, Saarnivaara L. Local bupivacaine-epinephrine infiltration combined with general anesthesia for adult tonsillectomy. Acta Otolaryngol 2005;125:972–975. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espitalier F, Remerand F, Dubost A-F, Laffon M, Fusciardi J, Goga D. Mandibular nerve block can improve intraoperative inferior alveolar nerve visualization during sagittal split mandibular osteotomy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2011;39:164–168. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatellier A, Dugué AE, Caufourier C, Maksud B, Compère JF, Bénateau H. Inferior alveolar nerve block with ropivacaine: effect on nausea and vomiting after mandibular osteotomy. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac 2012;113:417–422. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh K, Ohashi A, Kumagai M, Hoshi H, Otaka K, Joh S. Severe Bradycardia Possibly due to a local anesthetic oral mucosal injection during general anesthesia. Case Rep Dent 2015;2015:896196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, Julius D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 2009;139:267–284. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets HJ, Kievit J, Dulfer FT, van Kleef JW. Endocrine-metabolic response to abdominal aortic surgery: a randomized trial of general anesthesia versus general plus epidural anesthesia. World J Surg 1993;17:601–606. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi GP, McCarroll SM, O'Brien TM, Lenane P. Intraarticular analgesia following knee arthroscopy. Anesth Analg 1993;76:333–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jebeles JA, Reilly JS, Gutierrez JF, Bradley EL, Kissin I. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy pain reduction by local bupivacaine infiltration in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1993;25:149–154. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Strong JA, Meij JTA, Zhang J-M, Yu L. Neuropathic pain: early spontaneous afferent activity is the trigger. Pain 2005;116:243–256. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chigurupati K, Vemuri NN, Velivela SR, Mastan SS, Thotakura AK. Topical lidocaine to suppress trigemino-cardiac reflex. Br J Anaesth 2013;110:145. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohluli B, Schaller BJ, Khorshidi-Khiavi R, Dalband M, Sadr-Eshkevari P, Maurer P. Trigeminocardiac reflex, bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy, gow-gates block: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011;69:2316–2320. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury T, Sandu N, Schaller B, Meuwly C. Peripheral trigeminocardiac reflex. Am J Otolaryngol 2013;34:616. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwly C, Chowdhury T, Sandu N, Reck M, Erne P, Schaller B. Anesthetic influence on occurrence and treatment of the trigemino-cardiac reflex. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e807. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken G, Houston P, Lefebvre G. Guideline for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2008;30:600–607. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouloux GF, Punnia-Moorthy A. Bupivacaine versus lidocaine for third molar surgery: a double-blind, randomized, crossover study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999;57:510–514. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WI, Kendrick RW, Ramsay‐Baggs P, McCaughey W. The effect of pre-operative administration of bupivacaine compared with its postoperative use. Anaesthesia 1997;52:1212–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman HL, Harpavat S, Wu S, Allred EN, Berde C. Postoperative pain and other sequelae of dental rehabilitations performed on children under general anesthesia. Pediatr Dent 2008;30:111–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgain J-L. Anesthésie-réanimation en stomatologie et chirurgie maxillofaciale. EMC − Anesth-Réanim 2004;1:2–24. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Laxenaire MC, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Widmer S, et al. Substances anesthésiques responsables de chocs anaphylactiques. Enquête multicentrique française. Ann Fr Anesth Réanim 1990;9:501–506. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod NMH, Davies BJB, Brennan PA. Management of patients at risk of bisphosphonate osteonecrosis in maxillofacial surgery units in the UK. Surgeon 2009;7:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM, Peytcheva E. The impact of nonresponse rates on nonresponse bias: a meta-analysis. Public Opin Q 2008;72:167–189. [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Age of surgeons. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Surgical training. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Knowledge of the anaesthetist's work on intraoperative and post-operative pain control. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Frequency of local anesthesia (LA) infiltration during general anesthesia (GA) by surgeons. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Reasons why practitioners do not infiltrate local anesthesia (LA) during a general anesthesia (GA). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Frequency of local anesthesia (LA) infiltration in relation to the type of act performed under general anesthesia (GA). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.