| Issue |

J Oral Med Oral Surg

Volume 31, Number 2, 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 13 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2025018 | |

| Published online | 03 June 2025 | |

Original Research Article

Tobacco cessation education through peer-to-peer role-playing: implications for dental students’ future clinical practice. A pilot study

1

Nantes Université, Department of Oral Surgery, UFR Odontologie, CHU Nantes, PHU4 OTONN, Nantes, France

2

Nantes Université, Oniris, University of Angers, CHU Nantes, INSERM, Regenerative Medicine and Skeleton, RMeS, UMR 1229, 1 place Alexis Ricordeau, 44042 Nantes, France

3

Nantes Université, Department of Prosthetic Rehabilitation, UFR Odontologie, CHU Nantes, PHU4 OTONN, Nantes, France

4

Nantes Université, Department of Paediatric Dentistry, UFR Odontologie, CHU Nantes, PHU4 OTONN, Nantes, France

5

Engineering student in bioengineering and biotechnologies, Polytech Marseille, Parc scientifique et technologique de Luminy, 163 avenue de Luminy, 13009 Marseille, France

* Correspondence: anne-gaelle.chaux@univ-nantes.fr

Received:

2

January

2025

Accepted:

2

April

2025

Objectives: To assess the impact of a course incorporating role-playing on undergraduate dental students' satisfaction, knowledge, and attitudes toward tobacco cessation counseling. Methods: A pilot study was conducted at a French dental school between September 2022 and March 2023. Overall, 28 fourth- and fifth-year dental students participated in a three-step course on tobacco cessation counseling which included a theoretical component and role-playing sessions. Kirkpatrick’s four-level model was used to assess educational outcomes immediately after the theoretical course (levels 1 and 2) and 6 months later (levels 3 and 4). Results: The level 1 evaluation showed that most students were satisfied with the course (mean score: 4.7/5) and would use their knowledge in their future practice. For level 2, knowledge was significantly increased (+ 36.7%) following the course and was maintained at 6 months (p=0.015). Levels 3 and 4 assessed clinical behaviour and practice regarding tobacco cessation counselling and showed a significant increase in counseling (+28.7%) and in the prescription of tobacco substitutes (+ 48.6%) at 6 months (p=0.042 and 0.041, respectively). Conclusions: The study demonstrated the effectiveness of a role-playing-based course in terms of satisfaction, knowledge, and clinical behavior toward tobacco cessation counselling with sustained knowledge retention over time.

Key words: Dental students / simulation / tobacco cessation

© The authors, 2025

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Because smoking negatively affects oral health, and as approximately 70% of smokers visit a dentist every year, dentists could play a key role in tobacco cessation counselling [1]. Moreover, dentists are sometimes the first to notice tobacco-related damage such as oral mucosal lesions and they can provide timely motivation and information for tobacco cessation to their patients [2].

The teaching of tobacco cessation counseling is gradually developing, as about one third of medical schools in the United States [3] or in the United Kingdom [4] offer interactive courses on tobacco cessation counseling. Recently, there has been increasing interest in incorporating tobacco cessation counseling into dental curricula [5–8]. Students are generally aware of the benefits of tobacco cessation, the risks of smoking, their professional responsibility to help patients quit smoking, and the part they play as role models [9]; however, only a few students have received theoretical or practical training on tobacco cessation counseling [4,10].

The development of interactive learning in tobacco cessation counseling (i.e. role-playing, standardized patients, traditional courses, online courses, or a combination of modalities) has been shown to be effective among health professionals such as nurses and pharmacists [10,11]. Only few experiences on this topic have been reported in dental education [8–12]. Among the current interactive methods, peer role-playing seems particularly interesting because it is easy to organise, free of charge, and widely studied in other contexts. Its effectiveness has already been shown in a study on tobacco cessation training in dentistry [5]. These encouraging data need to be confirmed in dental education. Furthermore, its potential impact on clinical practice using a specialised model.

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of a course including role-playing sessions, in terms of satisfaction, knowledge, and attitudes toward tobacco counseling, among students of a French Dental School, immediately and 6 months after the course, using the Kirkpatrick evaluation model.

Material and methods

Study design

This pilot study was conducted at the Dental School of Nantes between September 2022 and March 2023. The study was approved by the ethics committee for non-interventional studies (CEDIS) of Nantes University (IRB: IORG0011023) under reference number 02052022.

Participants

Eligible participants were fourth- and fifth-year students who volunteered for an optional course on tobacco cessation counseling and prescription of tobacco substitutes. At the time of the study, the fourth-year students had just started their clinical work, while the fifth-year students had been treating patients for over 1 year. Each participant gave informed consent.

Learning models

The aim of the course was to provide students with behavioural skills and pharmaceutical knowledge to help patients in tobacco cessation. The course was structured in three steps. After a 2-hour lecture in which students learned about the mechanisms of tobacco addiction and dependence, how to prescribe nicotine substitutes, and how to communicate with the patient using motivational interviewing (including the As (ask − advise − assess − assist − arrange) [13] and the 5-Rs (relevance − risks − rewards − roadblocks − repetition) [14]), the students were asked to prepare a scenario for the next session in small groups (four students per group). To help them, several documents were made available, such as the learning course, web links to educational websites (i.e., tabac-info-service.fr), videos and documents on motivational interviewing, and even scientific papers. All of these documents remained accessible to the students throughout the duration of the course and for 1 year following the course. The scenarios were sent to the teacher and harmonised to fit learning objectives. They were then randomly assigned to the different groups (a group could not perform its own scenario). After 2 months, two simulation sessions (role-playing) were performed. In each small group, one student played the patient, one played the dentist, and the other two played the evaluators, using the French National Authority for Health (HAS) guidelines [15]. The session followed the HAS guidelines for simulation: a simulation session was planned with a briefing; the session was held; evaluation was performed first by the two actors, then by the two evaluators, then by the whole group, finally by the teacher [15]. The session finished with a debriefing assessing verbal and non-verbal communication and adherence to motivational interviewing.

Evaluation design

Kirkpatrick’s four-level model was used to evaluation of the effectiveness of the simulation in tobacco cessation counselling (Fig. 1) [16].

Before the course, two questionnaires (Q1 and 2) were completed: Q1 (knowledge), Q2 (clinical practice) in tobacco substitute prescription and counseling. After the course, a new Q1 was completed along with an evaluation of the course questionnaire (Q3). Six months later, Q1 was filled out again along with a new evaluation of the clinical practice questionnaire (Q2).

Level 1 (reaction) of Kirkpatrick’s model assessed the satisfaction scores of the students at the preclinical stage immediately after the training course, using Q3. Level 2 assessed knowledge gain at the preclinical stage before and immediately after the course, using Q1. Levels 3 (behavior) and 4 (clinical practice and outcomes) measured the application of the knowledge learned and the students' behavior in the clinical outcomes at six months, using Q2.

|

Fig. 1 Design for the Kirkpatrick’s evaluation of a course on tobacco cessation in dental practice. A pilot study, France, 2022–2023. Q: questionnaire; KL: Kirkpatrick’s level. Level 1: reaction; level 2: learning; level 3: behaviour; level 4: results. |

Questionnaires

The knowledge questionnaire (Q1) was composed of 10 questions on tobacco addiction and tobacco substitute prescription, with a binary response (true/false), leading to a total score of 10 points. The clinical practice questionnaire (Q2) was composed of eleven closed-ended questions evaluating students' counselling and prescribing behaviour in terms of patient counseling and prescription of nicotine substitutes. The evaluation of the course questionnaire (Q3) comprised eight closed questions and four open questions to assess the learning process. All response options for the closed questions in Q2 and Q3 used a five-point Likert scale (5 = very satisfied to 1 = not at all satisfied) whenever possible and open-ended questions for items related to the students' future practice.

Statistical analysis

Data from the completed questionnaires were imported into Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corporation, Issy les Moulineaux, France) for descriptive analysis. For each observed variable, scores and percentages were calculated along with the mean ± standard deviation (SEM). Student’s t-test were used to compare the data before and after intervention. Results were considered statistically significant at the level of p<0.05.

Results

Participants

Of the twenty-eight dental students included in the study, fifteen were in their fourth year (eight women and seven men, sex ratio: 0.9) and thirteen were in their fifth year (eight women and five men, sex ratio: 0.6). No student was lost to follow-up during the six months of the study.

Level 1 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: reaction

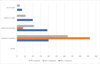

Overall, considering all twelve questions in the evaluation of the course questionnaire (Q3) using a Likert scale, students were satisfied with the teaching, with a mean score of 4.7/5. The results for objectives, length, rhythm, usefulness, activities, and interactivity are shown in Table I. One student (3.6%) found the course too short and one (3.6%) thought it needed more sessions. The need to be flexible, the simulation (role-playing), the interactivity, and the different approach to communicating with patients were appreciated as strong tools in learning how to propose tobacco cessation. Most students asked for flyers or written notes to help them prescribe tobacco substitutes in clinical practice after the end of the course. In total, 64.3% of all the students (n=18) reported that they would use their newly acquired knowledge in clinical practice within three months, 21.4% (n=6) within six months. 10.7% (n=3), all in the fourth year, declared that they would use their knowledge within twelve months (Fig. 2); all of these students were in their fourth year of study. One student (3.6%) did not answer. It appeared that the more experienced students (fifth year) would use their knowledge sooner. The student feedback during the structured debriefings was overwhelmingly positive, with twenty-seven positive and one negative comment.

Level 1 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: reaction in immediate evaluation of the course on tobacco cessation in dental practice, overall and by education level. A pilot study, France, 2022–2023. Data are shown as responses for each point of the Likert scale (from 1 = not satisfied at all to 5 = very satisfied), for the whole group and for 4th- and 5th-year students.

|

Fig. 2 Immediate post-course reaction: time interval for using knowledge in clinical practice after the course on tobacco cessation in dental practice, reported by students and by education level. A pilot study, France, 2022–2023. The question was: “In which time interval would you use what you have learned during this course?”. Data are shown as percentages of responses. |

Level 2 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: learning

The role-play learning improved knowledge scores (pre- vs. post-course immediate knowledge score) for all groups (Fig. 3). For all students, both fourth and fifth year, there was a 36.7% increase in the knowledge score [7.4/10 (5–10; SEM: 1.40) vs. 8.8/10 (7–10; SEM: 0.86), p=0.015]. For the fourth-year students, the increase was 48.9% [5.7/10 (2–8; SEM: 0.77) vs. 8.5/10 (7–9; SEM: 0.63), p=0.012], while for the fifth-year students, the increase was 25.6% [7.2/10 (4–10; SEM: 1.40) vs. 9.1/10 (8–10; SEM: 0.86), p=0.019].

After six months, the mean knowledge score of all students, both fourth and fifth year, was 8.4 (6–10; SEM: 1.04). There was no statistically significant difference in knowledge scores immediately after the course and six months later (p=0.052). For fourth-year students, the mean knowledge score was 8.23 (6–10; SEM: 1.24). There was no statistically significant difference in knowledge scores immediately after the course and six months later (p=0.054). For the fifth-year students, the mean knowledge score was 8.5 (7–10; SEM: 0.79). There was a statistically significant difference (p=0.042) in knowledge scores immediately after the course and six months later.

|

Fig. 3 Level 2 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: knowledge. Evolution of students' knowledge over time, overall and by education level. A pilot study to evaluate a course on tobacco cessation in dental practice, France, 2022–2023. Data are shown as the mean knowledge score out of 10. Scores obtained immediately after the course were compared to initial scores, and those obtained six months later were compared to immediate post-course scores. P-values are provided only when significant. |

Levels 3 and 4 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: behavior change and results at six months

All of the fifth-year students and 26.7% (n=4) of the fourth-year students had already informed their patients about tobacco cessation before the course (overall percentage: 60.7%). In the fourth-year group, only one student had already prescribed tobacco substitutes, whereas in the fifth-year group, four students had already prescribed tobacco substitutes, of whom two had written several prescriptions.

At six months, the clinical application of the course showed a significant increase of 28.7% in counseling (p=0.042) and 48.6% in prescription of tobacco substitutes (p=0.041) for all students. All (100%) fifth-year students conducted at least five counselling sessions, 92.3% (n=12) prescribed tobacco substitutes at least once. For fourth-year students, 86.7% students provided at least one counselling and 33.3% (n=4) prescribed tobacco substitutes at least once (Tab. II). Several barriers to tobacco cessation counseling were reported, mainly lack of time (seven students) and fear of the patient’s reaction as well as lack of motivation (seven students), without any difference between fourth- and fifth-year students.

Levels 3 and 4 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: clinical attitude and practice; perceived usefulness of the course. For clinical attitude and course usefulness, data are shown as the mean score out of a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = strongly agree). *p. = 0.003; **p. = 0.04; SEM: standard error of the mean.

Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of a tobacco cessation course including role-playing in dentistry. Based on the four levels of the Kirkpatrick model, we showed that this course had a positive impact on students' satisfaction, knowledge and clinical behaviour toward tobacco cessation counseling and their maintenance over time at six months.

Pedagogical model

A good program in tobacco cessation counseling should answer the following questions: What is the appropriate training level? How can rapport and communication skills be emphasised? and confidence through good communication skills? What should be the core level of knowledge? How should continuing education be provided [17]?

Peer role-play and standardised patient modules are both interactive methods that can be used to achieve these objectives. They increase communication skills, knowledge scores, and self-confidence [4,18,19]. Nonetheless, the high cost of a simulated patient module could be a limitation in public universities, as it includes the training of simulated patients and the payment of salaries and/or the standardized patients. According to Park et al., satisfaction with the course seemed to be identical for both methods in their study, with similar short- and long-term retention of information [4]. Nonetheless, they suggested that peer role-play was taken seriously [4]. This was not the case in our study, as students assumed their role with professionalism.

Some authors proposed multimodal learning courses [20,21]: a role-playing scenario with a standardized patient, combined with a seminar, testimonies, and written reflections of students and clinical care [22]; as well as interactive training sessions in small groups, combined with a standardized patient module [2]. Since online learning is more time-efficient and is preferred by students, its combination with another method [i.e., role-playing or Objective Structured Clinical Examination] could improve their skills and counseling performance [18,23]. The present tobacco cessation training course was also based on the hybrid classroom model with a mix of theoretical courses and role-playing.

Beyond the method, feedback is essential [24]. Some authors [2,18] proposed immediate feedback on standardized patient modules and/or role-playing modules through performance recording in order to boost the retention of knowledge. The feedback focuses on both verbal and nonverbal counseling skills. Antal et al. [2] proposed a three-step course: theoretical learning, role-plays (at least four), and then video feedback of the role-play performance in small groups to gain experience and have professional feedback on their performance without any risk to the patient. There are no guidelines regarding the time interval for debriefing [25]. In this study, immediate feedback was given. Students appreciated immediate feedback… to share impressions and stress they may have felt during the simulation.

Level 1 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: high student satisfaction

Overall, twenty-seven out of twenty-eight students (96.4%) were satisfied or very satisfied with the course. One negative comment about session length, but there was overwhelming support for interactivity and active learning. In the study by Antal et al. [2], with a similar design combining theoretical and practical sessions, more than 90% of the students were satisfied with the course.

Level 2 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: knowledge enhancement

In our study, knowledge was significantly increased by the course and it was maintained at six months. It has been shown that the short- and long-term effects of peer role-play and standardized patient methods on knowledge retention remain at eight months [4]. Thus, peer role-playing seems to be a valuable option for tobacco cessation education.

The fourth-year students tended to maintain their level of knowledge, which supports the saying “the earlier the course, the better the retention” [24].

Levels 3 and 4 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: improvement of attitudes toward tobacco cessation counseling and improvement of clinical practice

In our study, clinical habits regarding tobacco cessation counseling and prescription were significantly improved by the course. Generally, without tobacco cessation courses, the lack of knowledge and skills is the main barrier reported in the literature for providing tobacco cessation counseling (90.5–85.7%) [10]. Uti et al. showed that an interactive tobacco cessation counseling course resulted in a decrease in the perceived barriers [8]. After attaining the knowledge and skills, the remaining barriers reported in our study were lack of time and fear of the patient’s reaction, both for fourth- and fifth-year students. Lack of time is one of the barriers to tobacco counseling reported by postgraduate dentists, along with patient resistance, not being reimbursed, and not knowing where to refer the patient [26]. We can assume that students' uncertainty about their legitimacy to prescribe tobacco cessation counseling and prescribing nicotine substitutes, which would explain the fear reported by some of them.

Nonetheless, students significantly increased counselling and nicotine prescribing after the course. Movsisyan et al. [20], despite the proven effectiveness of their training course in terms of knowledge, smoking status assessment, and counseling strategies, found no improvement in the prescription of tobacco substitutes at six months after the course. Carson et al. [27] confirm that after training, health professionals are more likely to provide tobacco cessation counseling, but there is no difference for tobacco replacement therapy. This difference with our study could be explained by the active learning, the spread of the course over four months (from the first session to the end of the curriculum), and the availability of all training documents after the course.

Strength of the study

One of the strengths of the study is that Kirkpatrick model were investigated in dental students working in the university clinic, with an evaluation of the impact of the course on their clinical behavior at six months. Role-playing can be challenging but it can also be a source of motivation for students. Antal et al. [2] report that even unmotivated students were quickly engaged in the learning course.

Limitations of the study

The main limitation of the study was the low number of students involved involved in the course, which limits the overall statistical significance and the representativeness of the sample. Moreover, as the included students volunteered to participate in the course, they were probably more concerned by tobacco cessation counselling, which could introduce a bias and artificially enhance the results. It would also have been interesting to compare the impact of the course with a control group receiving a traditional course (i.e., lecture) on tobacco cessation counseling. Nonetheless, due to the fact that it was the first time such a course was proposed, there was no reference learning course available, and thus comparison was not possible.

The structure of the course could also be improved: As seen previously, immediate feedback is essential, but video-based feedback could also enhance students' self-evaluation and thus the benefit of the course. Structuring the course in an OSCE format could further aid in evaluating students' performance [5]. The course could further be combined with clinical observations of tobacco cessation consultations, which would reinforce the theoretical learning.

Conclusions and perspectives

This recently introduced course on tobacco cessation counseling was a success: twenty-eight students volunteered for the course in the first year (with a 96.4% satisfaction rate), and forty in the second year. The two pillars of the course are its multimodality, comprising a theoretical course and interactive role-playing sessions, and the feedback given to students after they have completed the scenarios. The course resulted in a significant improvement in knowledge, tobacco cessation counselling, and nicotine substitute prescription. The role-playing method (which combines role-playing and briefing/debriefing) helps to develop a non-judgemental and empathetic approach to care and helps to maintain knowledge over time. It seems to be an effective method for promoting empathy and a different way of communicating with patients [21], not only in tobacco cessation counseling but also in any difficult situation the patient may face.

Tobacco cessation counseling should also be considered a global educational objective, as even clinical supervisors have limited formal education [7] and do not always feel confident in helping students counsel patients. Furthermore, postgraduate dental professionals should follow continuing education courses: According to Walsh, dentists who are trained in tobacco cessation counseling significantly increase the number of prescription of nicotine substitutes in their practice [12]. Education should also be expanded to include other forms of addiction [22].

Regarding the course itself, combining role-playing or a standardised patient module in an interdisciplinary course could improve the counseling skills and self-efficacy of students. This could expand dental students' perceptions of interprofessional education [28].

Funding

This research did not receive any specific funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availability statement

The questionnaires are available on request.

References

- Garvey A.J. Dental office interventions are essential for smoking cessation. J Mass Dent Soc 1997;46:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antal M, Forster A, Zalai Z, Barabas K, Spangler J, Braunitzer G, Nagy K A video feedback-based tobacco cessation counselling course for undergraduates − preliminary results. Eur J Dent Educ 2013;17 (1): e166–e172. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson L.L, Blumenthal D.S, Dever A, McGrady G. A web-based smoking cessation and prevention curriculum for medical students: why, how, what, and what next. Drug Alcohol Rev 2006;25:39–47. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K.Y, Park H.K, Hwang H.S. Group randomised trial of teaching tobacco-cessation counselling to senior medical students: a peer role-play module versus a standardised patient module. BMC Med Educ 2019;19:231. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romito L, Schrader S, Zahl D Using experiential learning and OSCEs to teach and assess tobacco dependence education with first-year dental students. J Dent Educ 2014;78 (5): 703–713. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton J.A, Carrico R.M, Myers J.A, Scott D.A, Wilson R.W, Worth C T. Tobacco cessation treatment education for dental students using standardised patients: randomised controlled trial. J Dent Educ 2014;78 (6): 895–905. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett M.R, Baba N.Z Improving tobacco dependence education among the Loma Linda University School of Dentistry faculty. J Dent Educ 2011;75 (6): 832–838. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uti O, Sofola O Impact of an educational intervention on smoking counselling practice among Nigerian dentists and dental students. Niger J Clin Pract 2015;18 (1): 75–79. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yentz S, Klein R.J, Oliverio A.L, Andrijasevic L, Likic R, Kelava I, Kokic M The impact of tobacco cessation training of medical students on their attitude towards smoking. Med Teach 2012;34 (11): 1000–1000. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn M, Ahn Y, Park H, Lee M Simulation-based smoking cessation intervention education for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 2012;32:868–872. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffouh El Hajj M, Awaisu A, Kheir N, Haniki Nik Mohamed M, Shami Haddad R, Ahmed Saleh R, Mohammed Alhamad N, Mohd Almulla A, Mahfoud Z.R Evaluation of an intensive education program on the treatment of tobacco-use disorder for pharmacists: a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2019;20:25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh M.M, Belek M, Prakash P, Grimes B, Heckman B, Kaufman N, Meckstroth R, Kavanagh C, Murray J, Weintraub J.A, Silverstein S, Gansky S.A The effect of training on the use of tobacco-use cessation guidelines in dental settings. J Am Dent Assoc 2012;143 (6): 602–613. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treating tobacco use and dependence − PHS Clinical Practice Guideline. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/5steps.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Treating tobacco use and dependence − PHS Clinical Practice Guideline. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/5rs.pdf [Google Scholar]

- HAS. Guidelines for good practice in health simulation. Available at: https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2024-04/spa_181_guide_bonnes_pratiques_simulation_sante_cd_2024_03_28.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kurt S. Kirkpatrick model: four levels of learning evaluation. Educational Technology. Available at: https://educationaltechnology.net/kirkpatrick-model-four-levels-learning-evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Davis J.M, Ramseier C.A, Mattheos N, Schoonheim-Klein M, Compton S, Al-Hazmi N, Poluchronopoulou A, Suvan J, Antohé M.E, Forna D, Radley N Education of tobacco use prevention and cessation for dental professionals − a paradigm shift. Int Dent J 2010;60 (1): 60–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenschutz H, Ross P, Purkiss J, Yang J, Middlemas S, Lypson M Standardised patient instructor (SPI) interactions are a viable way to teach medical students about health behaviour counselling. Pat Educ Couns 2011;84:271–274. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boykan R, Blair R, Baldelli P, Owens S Using motivational interviewing to address tobacco cessation: two standardised patient cases for paediatric residents. MedEdPORTAL 2019;15:10807. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movsisyan N.K, Petrosyan V, Abelyan G, Sochor O, Baghdasaryan S, Etter J.F Learning to assist smokers through encounters with standardised patients: an innovative training for physicians in an Eastern European country. PLoS ONE 2019;14 (9): e0222813. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B.A, Chewning B.A Evaluating pharmacists' ability to counsel on tobacco cessation using two standardised patient scenarios. Pat Educ Couns 2011;83 (3): 319–324. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brondani M.A, Pattanaporn K Integrating issues of substance abuse and addiction into the predoctoral dental curriculum. J Dent Educ 2013;77 (9): 1108–1117. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauerer E, Tiedemann E, Polak T, Simmenroth A Can smoking cessation be taught online? A prospective study comparing e-learning and role-playing in medical education. Int J Med Educ 2021;12:12–21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff J.P, Morse K.J, Seelandt J, Gross I.T, Lydston M, Sargeant J, Dieckmann P, Allen J.A, Rudolph J.W, Kolbe M Debriefing methods for simulation in healthcare: a systematic review. Simul Healthc 2024;19(1S): S112– S121. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller A.C, Daniel R, Brooks D.R, Powers C.A, Brooks K.R, Rigotti N.A, Bognar B, McIntosh S, Zapka J Tobacco cessation and prevention practices reported by second- and fourth-year students at US medical schools. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23 (7): 1071–1076. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash P, Belek M.G, Grimes B, Silverstein S, Meckstroth R, Heckman B, Weintraub J.A, Gansky S.A, Walsh M.M Dentists' attitudes, behaviours, and barriers related to tobacco-use cessation in the dental setting. J Public Health Dent 2013;73 (2): 94–102. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson K.V, Verbiest M.E, Crone M.R, Brinn M.P, Esterman A.J, Assendelft W.J, Smith B.J Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;5:CD000214. [Google Scholar]

- Schwindt R, McNelis A.M, Agley J, Hudmon K.S, Lay K, Wilgenbusch B Training future clinicians: an interprofessional approach to treating tobacco use and dependence. J Interprof Care 2019;33 (2): 200–208. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cite this article as: Cloitre A, Clouet R, Hascoët E, Prud'homme T, Bodard C, Chaux A.-G. 2025. Tobacco cessation education through peer-to-peer role-playing: implications for dental students’ future clinical practice. A pilot study. J Oral Med Oral Surg. 31, 13: https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2025018

All Tables

Level 1 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: reaction in immediate evaluation of the course on tobacco cessation in dental practice, overall and by education level. A pilot study, France, 2022–2023. Data are shown as responses for each point of the Likert scale (from 1 = not satisfied at all to 5 = very satisfied), for the whole group and for 4th- and 5th-year students.

Levels 3 and 4 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: clinical attitude and practice; perceived usefulness of the course. For clinical attitude and course usefulness, data are shown as the mean score out of a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = strongly agree). *p. = 0.003; **p. = 0.04; SEM: standard error of the mean.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Design for the Kirkpatrick’s evaluation of a course on tobacco cessation in dental practice. A pilot study, France, 2022–2023. Q: questionnaire; KL: Kirkpatrick’s level. Level 1: reaction; level 2: learning; level 3: behaviour; level 4: results. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Immediate post-course reaction: time interval for using knowledge in clinical practice after the course on tobacco cessation in dental practice, reported by students and by education level. A pilot study, France, 2022–2023. The question was: “In which time interval would you use what you have learned during this course?”. Data are shown as percentages of responses. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Level 2 of Kirkpatrick’s evaluation model: knowledge. Evolution of students' knowledge over time, overall and by education level. A pilot study to evaluate a course on tobacco cessation in dental practice, France, 2022–2023. Data are shown as the mean knowledge score out of 10. Scores obtained immediately after the course were compared to initial scores, and those obtained six months later were compared to immediate post-course scores. P-values are provided only when significant. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.