| Issue |

J Oral Med Oral Surg

Volume 31, Number 2, 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 16 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2025017 | |

| Published online | 06 June 2025 | |

Educational Article

Nasal deformities in cleft lip and palate: an update for dental professionals

1

Oral surgery resident, University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

2

PhD, Associate Professor, Program Director of MDS-Oral Surgery, University of Sharjah, UAE

3

Prosthodontics resident, University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

* Correspondence: wala.ahmed@dr.com

Received:

17

December

2024

Accepted:

17

March

2025

Cleft lip and palate nasal deformities often lead to a lasting stigma for those affected, presenting unique challenges due to the complex nasal anatomy. The quality of life and daily activities of patients may be greatly impacted by these defects, which can impose numerous functional limitations. The complex nasal structure in these cases makes treatment difficult, and a range of protocols has been developed to address both appearance and function. The effectiveness of presurgical orthopaedics prior to surgical intervention is not conclusive. Although gingivoperiosteoplasty has an indirect effect on nasal deformity, alveolar bone grafting provides structural support for the nose. Long-term follow-up is essential to maintain satisfactory outcomes and prevent relapse. The cleft care team typically includes orthodontists, prosthodontists, and oral surgeons. However, nasal deformities, which are often associated with septal deviation and sagging of the nasal dome, tend to fall within the expertise of maxillofacial surgeons, plastic surgeons, or ENT specialists. This review may offer valuable insights for dental professionals streamlined to evaluating and managing of nasal deformities in patients with cleft lip and palate.

Key words: cleft nasal deformities / cheilognathopala-toschisis / cheilorhinoplasty / primary rhinoplasty

© The authors, 2025

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Nasal deformity associated with cleft lip is highly distinctive and remains a source of stigma for individuals affected by this condition. The prevalence of cleft lip and/or palate (CLP) ranges from 0.3 to 2.4 per 1,000 live births in regions such as Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Jordan [1].The birth prevalence of orofacial clefts was found to be higher in males compared to females, while isolated cleft palate was more commonly observed in females in most instances [1]. Rhinoplasty in CLP patients is among the most demanding surgical procedures. This is largely because it involves all layers of the nose, skin, cartilage, bone, and vestibular lining and often often complicated by scarring from previous surgeries. The resulting nasal deformity can significantly affect both appearance and function, with the severity ranging from subtle to extreme requiring a multidisciplinary approach. A cleft care team typically comprises orthodontists, maxillofacial surgeons, plastic surgeons, pedodontist, prosthodontists, speech therapists, audiologists, psychologists, and paediatricians. Prosthetic rehabilitation for CLP patients begins at birth and continues through adulthood [2–3] This narrative review is written for dental healthcare workers to provide dental professionals with an updated understanding of nasal deformities in CLP, highlighting the surgical challenges associated with their treatment.

Methods

For this review, an extensive literature search was conducted using indexed databases, including PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The literature search focused on key terms pertinent to nasal deformities in cleft lip and palate. The following terms were used for the search: “nasal deformity”, “cleft lip and palate”, “cleft rhinoplasty”, “management of cleft nose”, “cheilognathopalatoschisis”, “prosthetic treatment of cleft lip and palate” and “nasal molding”. The review followed PRISMA guidelines. The review was conducted between February 2024 and October 2024. To avoid bias, three authors independently conducted the literature search, each blinded to the others' results. Upon completion, findings were then consolidated and synthesised. The eligibility criteria included English language publication, period of publication between 2000 to 2024, full text articles and human studies. Any article with inadequate data, non-English language, animal or in vitro studies and duplicate studies was excluded.

Anatomy of the nasal structures

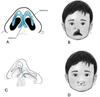

The nose consists of three distinct layers: the cutaneous layer, the osseocartilaginous framework, and the inner mucoperichondrium [4,5]. The cutaneous layer is the outermost layer of the nose, made up of skin that covers the entire nasal surface. The skin is thinner at the nasal dorsum and thicker (nasal dorsum) and thicker, with more sebaceous glands, at the lower part (nasal tip and alar regions) [6]. The innermost layer is the mucosal lining, also called the mucoperichondrium when it covers the cartilage and the mucoperiosteum when it covers the bones [7]. This layer consists of a moist, mucous membrane that helps to warm, humidify, and filter the air we breathe. The osseocartilaginous layer, which provides the primary structural support, is divided into the upper, middle, and lower vaults. In addition, several muscles are connected to the nasal base and lobule [5–6]. The tripod theory offers insight into the architecture of the nasal tip, base, and lobule [4,8,9]. According to this model, the right and left lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilage act as two legs of a tripod supporting the nasal tip, while the medial crura form the third leg (Fig. 1A1). The theory provides significant insights into the functioning of the nasal tip by identifying the various factors that influence its shape. In contrast, nasal deformities related to CLP are typically intricate, involving multiple structures within the nose. The fibers of the orbicularis oris muscle do not run in a transverse direction but instead curve upward along the edges of the cleft, terminating beneath the base of the columella on the medial side and below the alar base and periosteum of the pyriform rim on the lateral side [10,11]. This abnormal muscle insertion produces a bulge, along with distortion of the nasal ala, deflection of the nasal septum, and displacement of the anterior nasal spine [8,12] (Fig. 1B). The premaxillary platform is rotated outward and projected forward, while the lateral maxillary segment is positioned posteriorly, resulting in asymmetry at the nasal base. The lower border of the septum is displaced from the vomerine groove, twisting the nasal tip and columella [13]. Additionally, The columella is shortened unilaterally, with a deflection towards the non-cleft side. The nasal floor shows defects in the skin, muscle, and bone. The alar cartilage on the cleft side is flattened, more horizontally oriented, and stretched at an obtuse angle [14,15].

In the absence of alar cartilage bulging, the alar crease may extend over the nasal tip, producing a segmented appearance the alar crease to extend over the nasal tip, producing a segmented appearance. Additionally, the outward rotation of the alar base gives the nostril a flared look [12]. On the cleft side, the unsupported alar rim forms a soft tissue fold, further shortening the columella, which further shortens the appearance of the columella [10].

|

Fig. 1 A) The right and left lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilage act as two legs of a tripod supporting, the nasal tip, while the medial crura form the third leg. B) Note the discontinuity in the orbicularis oris muscle and the lip length discrepancy. C) Slumping and lateral displacement of the alar dome, as well as displacement of the nasal septum. D) Note the flat nasal tip, short columella, and lateral displacement of the alar cartilage. |

Types of nasal deformities associated with cleft lip

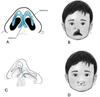

Nasal deformities associated with CLP vary by cleft type, size, and severity of the cleft. These deformities affect the nasal symmetry and contour, reflecting the cartilage and soft tissue disruption in nasal cartilage and soft tissues. The most prevalent abnormality in individuals with unilateral cleft lip is nasal asymmetry [11]. The nasal deformity typically affects one side of the nose. The most prominent features include asymmetry, where the nasal tip deviates towards the non-cleft side due to the abnormal attachment of the alar cartilage and displacement of the columella. Additionally, the nasal dome on the cleft side is usually flattened and lower than on the non-cleft side, resulting from underdevelopment and misalignment of the nasal cartilage [16]. The nasal base on the cleft side is often wider, caused by lateral displacement of the alar base. Furthermore, the nostrils on the cleft side tend to appear oblique or slanted, with the alar rim flared outward, further highlighting the asymmetry [16,17] (Fig. 1C).

Bilateral cleft lip affects both sides of the upper lip, resulting in distinct nasal deformities. These include a broad and flat nasal tip, caused by bilateral displacement and underdevelopment of the alar cartilages [11]. The columella is often shortened or absent due to lack of support from the cleft lip segments and the abnormal positioning of the nasal cartilages. Additionally, the alar base is typically widened, because lateral displacement of the alar cartilages occurs on both sides [11,18]. The nasal bridge may also appear collapsed or underdeveloped, resulting from insufficient structural support from the underlying nasal bones and cartilage [19] (Fig. 1D).

Functional limitations

Nasal deformities associated with cleft lip present can lead to multiple functional challenges that significantly affect the patient's quality of life, particularly nasal obstruction, difficulties with speech, and recurrent infections [20]. The misalignment and underdevelopment of the nasal structures often lead to partial or complete obstruction of the nasal passages, which directly affects breathing and airflow. In cases of severe obstruction, patients may experience chronic mouth breathing, reduced oxygen intake, and overall discomfort, which can hinder normal respiratory function and lead to sleep disturbances, including sleep apnea [20,21]. Mouth breathing can significantly impact oral health, leading to a variety of dental and periodontal issues. The reduction of saliva production or xerostomia is one of the complication of mouth breathing which can result in increased risk of dental caries, gingivitis, periodontitis and increasing the risk of infections such as oral candidiasis [22]. Mouth breathing, especially in children, can affect the development of facial and dental structures. Chronic mouth breathing causes the tongue to rest in an abnormal position, which may result in improper growth of the jaw and dental arches [23,24]. These deformities also have a profound impact on speech, as the altered structure of the nasal cavity can disrupt normal airflow and resonance. This often results in hypernasality, where excessive air escapes through the nose during speech, and articulation issues, as the misaligned structures impede the clear production of certain sounds [25]. This can lead to difficulties in communication and may require long-term speech therapy to address these challenges. Many cleft lip patients experience frustration with their speech clarity, particularly during childhood, when communication skills are rapidly developing [21,25].

In addition to breathing and speech issues, the structural abnormalities caused by cleft nasal deformities increase susceptibility to recurrent nasal infections and chronic sinusitis. Impaired drainage and ventilation of the nasal cavities can result in mucus buildup, leading to frequent infections [26]. These infections may result in discomfort, persistent congestion, and inflammation, which can make it harder for the patient to breathe and increase complicate the treatment of this condition. A patient's quality of life can be improved, and functional outcomes can be improved by early and complete treatment of cleft nasal deformities [20]. This is because speech difficulties, nasal obstruction, and a higher risk of infection are common symptoms of the illness [27].

Management of CLP-related nasal deformities

The management of CLP-related nasal deformities begins in early childhood and continues into later stages of life. Treatment involves multiple phases, including the pre-surgical stage, surgical interventions, postoperative care, and follow-up. This long treatment pathway demands meticulous planning and a multidisciplinary approach to ensure optimal outcomes.

Orthopedics and Pre-surgical stage

Presurgical infant orthopedic (PSIO) is a commonly used orthopedic technique for correcting cleft deformities before surgery. The method is based on the theory that the cartilage in infants contains higher levels of hyaluronic acid, making it more pliable and moldable [25,28]. By around three months of age, the cartilage becomes more rigid with reduced plasticity. PSIO significantly improves nasal symmetry by elongating the columella, supporting the alae, narrowing the cleft, and restoring the alveolar arch, resulting in both immediate and long-term improvements [3,24]. It operates on the principles of passive molding and negative sculpting of the alveolus, lip, and nasal tissues. An initial impression is taken, and custom plates are created [3,29]. These plates are modified by adding and removing material in specific areas, a process known as negative sculpting. The goal is to achieve alignment and symmetry of the maxillary alveolar segments and to address the nasal deformity by molding the cartilage into its correct anatomical position [28–31].

Impression Making: A heavy-bodied polyvinyl siloxane material is used for the initial impression. The infant is positioned prone to keep the tongue forward, allowing saliva and material to drain, reducing the risk of aspiration. This should be done in a hospital with an anesthetist present to handle any potential airway emergencies. After the impression is made, the oral cavity is checked for any remaining material [3,32].

Alternatively, digital workflow to provide PSIO is an advanced, technology-driven approach to traditional PSIO treatment for CLP patients [33]. Unlike conventional methods that rely on manual molding devices, digital PSIO uses cutting-edge digital tools such as 3D imaging, computer-aided design (CAD), and 3D printing to design and produce customized orthopedic devices with improved precision and efficiency [34]. This digital approach offers several benefits over traditional PSIO techniques such as precision and customization, improved comfort for infants, avoidance of general anaesthesia, time efficiency and predictability of the outcome [33,35] (Fig. 2A).

Device Fabrication: The molding plate is crafted from clear methyl methacrylate, lined with soft denture material, and fitted to a dental stone model. The borders are trimmed and smoothed to prevent ulcers, and the oral surface is polished for retention, ensuring it doesn't extend into the cleft area [3,32].

Insertion and Molding: The molding plate is worn full-time and removed only for cleaning and hygiene purposes to prevent infection and check for ulcers [3]. The infant's suckling ability should be assessed with the plate in place to monitor for gagging. Surgical tape secures the plate to both cheeks, pulling the anterior flange in a posterosuperior vector for activation [3]. The tape is applied over wound dressing material like micropore tape to protect the skin to protect the skin and is changed daily, starting on the non-cleft side and then being pulled to the cleft side. Weekly follow-ups are necessary to assess retention and alveolar segment changes [3,32].

Molding Plate Modification: Selective grinding of acrylic material is performed in the areas where alveolar segments are expected to move. At the same time, soft denture lining material is selectively added to guide the segments toward the midline. In bilateral cleft patients, the premaxilla is retracted and rotated to align with the normal maxillary arch [3]. Ideally, a 1–2 mm gap remains between alveolar segments for optimal surgical results. Once the maxillary alveolar segments are approximated, nasal molding begins. A stainless-steel wire is added to the molding plate, extending into the nose in a “swan neck” shape, with a small loop to hold a bilobed intranasal acrylic component covered with a soft denture liner (Figs. 2B and 2C). The nasal stent is inserted 3–4 mm inside the ala and gently lifted toward the nasal dome until slight blanching occurs. As the baby suckles, blanching of the nasal tip indicates that the appliance is active. Lip taping continues even after the nasal stent is added [3,32].

Three-dimensional (3D) photography, or stereophotogrammetry, has been employed to accurately quantify the morphological changes that occur throughout the treatment process. The integration of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) technology into the fabrication of PSIO appliances has led to a production method that is more cost-effective, efficient, and user-friendly compared to traditional techniques [36].

|

Fig. 2 A) Digital impression-taking for fabrication of PSIO. B and C) Acrylic plate with a nasal stent extending from the vestibular aspect. B is for unilateral cleft, and C for bilateral cleft deformities. |

Surgical stage

Surgical correction of nasal deformities in cleft lip patients plays a crucial role in improving both functionality and aesthetics. Primary treatment of the nose during lip repair and the postoperative use of nasal conformers has gained considerable popularity in recent years due to its potential for achieving early restoration of nasal symmetry [37–38] (Fig. 3A). The procedure aims to reposition the alar cartilage and lengthen the columella both of which are often significantly affected by cleft lip deformities. By early correction of these nasal conditions, surgeons aim to create a more balanced and harmonious nose, which can provide proper facial growth and lessen the need for more extensive corrections in the future [39]. Despite the benefits of early surgical intervention, one significant challenge is the frequent occurrence of relapse, mainly due to the elastic characteristics of the deformed alar cartilage. As time passes, this cartilage often returns to its initial shape, which can affect the surgical outcomes and lead to the need for additional interventions [37] (Fig. 3B).

When to perform a septal repair is a topic of discussion among surgeons. there are several theories regarding whether the septum should be corrected at the time of main surgery or at a later developmental stage. While some contend that early septal correction can improve nasal function and appearance, others support postponing septal correction until later in childhood or adolescence to avoid any potential interference with facial growth. The difficulty of correcting nasal deformities caused by cleft lip is demonstrated by this dispute [39,40].

Burgaz et al. investigated the effect of PNAM in combination with primary rhinoplasty on unilateral CLP patients. Using three-dimensional analysis, the study demonstrated significant improvements in several key nasal parameters, including nasal projection, columella length, nasal symmetry, and nasal width. Although the results of the study emphasize the effectiveness of PNAM and primary rhinoplasty which led to early improvements in nasal aesthetics and function, a systematic review and meta-analysis have questioned its usefulness, concluding that this intervention should not be routinely included in treatment plans until further studies provide clearer evidence of its impact [41,42].

As the patient ages, additional intervention are often needed, which is where secondary rhinoplasty comes in. The goal of secondary rhinoplasty, which is usually performed in late childhood or adolescence, is to enhance the appearance and functionality of the nose. Techniques include altering the nasal tip and alar base to create a more balanced and symmetrical nasal contour, lengthening the columella to increase nasal projection, and cartilage grafting to offer more support. More accurate alterations that correspond with the patient's facial growth and development are possible with this subsequent procedure [43,44]. Cartilage grafts are commonly used to reconstruct the nasal framework and correct asymmetry, providing structural support for cleft nasal deformities. Osteotomies are often performed to reposition the nasal bones, particularly in cases of bilateral clefts, where malpositioning is frequently seen. Problems with tip projection and rotation are addressed by nasal tip refinement; these issues frequently necessitate complex cartilage manipulation in order to get the intended functional and aesthetic results. Furthermore, eliminating septal deviations—a major cause of nasal airway obstruction—through septoplasty is essential for restoring nasal symmetry and function [40,45]. Post cleft rhinoplasty, nasal conformers are used to stabilize and support the corrected nasal structure ensuring that the nasal cartilage and soft tissues maintain their intended shape during the healing process. It also helps in minimizing scar tissue contraction, maintain the patency of the nasal airway and prevent relapse [37,38].

Alveolar bone grafting (ABG) becomes necessary when the cleft involves the alveolar ridge. This surgery gives the nasal base the vital structural support it needs. ABG provides an optimal surgical outcome by enhancing nasal symmetry and stability and facilitating dental alignment by strengthening the bony architecture [44–45]. When combined, these surgical procedures provide patients with cleft lip defects with a nasal structure that is symmetrical, aesthetically accepted [46]. ABG involves the surgical placement of bone, usually harvested from the iliac crest, into the alveolar cleft. The goal is to stabilize the dental arch, improve nasal symmetry, and restore the maxilla's continuity so that teeth can emerge normally [46] (Fig. 4). ABG comes in two principal varieties: primary and secondary.

The primary ABG was originally described as a procedure performed during the closure of the lip and palate, prior to the eruption of primary teeth, typically well before the age of 2 years [47]. Currently, the primary ABG is performed in early childhood, typically before the eruption of the primary teeth, between 2 and 5 years of age [48]. It allows for Early closure of the alveolar cleft, provide early continuity of the alveolar ridge, improve nasal symmetry, and avoid future collapse of the dental arch. It may help with speech development by improving oral and nasal separation [48]. It can help avoid or reduce the need for orthodontic expansion later in life as well as improving the overall aesthetics of the nasal and dental structures [47,48].

The secondary ABG has historically been performed prior prior to the eruption of the canine. However, the early secondary ABG is now typically carried out before the eruption of the permanent central incisor, providing optimal periodontal outcomes for the teeth adjacent to the cleft [49]. The main aim is to provide adequate bone support for the eruption of permanent teeth, particularly the canine, into the cleft site [46,50]. It restores the continuity of the dental arch which enable orthodontic treatment to align teeth properly [48]. In addition, it helps to stabilize the maxillary arch and improve facial aesthetics by enhancing lip and nasal support [46–53].

|

Fig. 3 A) Nasal Conformer. B) Note the widened alar base post-primary lip and nose repair. |

|

Fig. 4 Reflection of the full mucoperiosteal flap, exposure of alveolar bone and ABG in the cleft defect. |

Postoperative care and long-term outcomes

The majority of the success following cleft nose surgery is contingent upon the postoperative management. Since nasal stents are often needed to support the recently repaired nasal passages and prevent them from collapsing, they are an integral part of therapeutic care [13]. These stents help retain the repaired shape of the nose by keeping the airways open and functional during the healing process. Effective scar care is crucial because, if left untreated, scar tissue may may shrink and cause the nose to change in appearance as well as function. The use of techniques like silicone sheeting, scar massage, or steroid injections can help with this by reducing the production of scars, accelerating healing, and safeguarding the results of surgery [53].

Monitoring growth is particularly important in younger patients who are still developing. Since facial growth continues into adolescence, close observation is needed to assess how surgery influences overall facial development and nasal symmetry [26]. Surgeons can identify problems early with routine follow-ups, such as potential nasal structural alterations in the growing child, allowing for prompt correction if needed. If growth is not tracked, there may be a relapse or further corrective actions that become necessary [26,46]. Long-term results of cleft nose surgery are analysed, and findings indicate that while many patients have significant functional and cosmetic benefits, modifications are often necessary. Patients may experience a recurrence of deformities or functional problems as a result of growth-related changes that can affect nasal shape [53]. Relapse is not unusual since the nose can return to its preoperative state due to the elastic nature of nasal cartilage and continuous facial growth. Because of this, cleft patients usually need several surgeries in their lifetime in order to maintain the best possible shape and function of their noses [26]. The need of continuous treatment and monitoring in controlling cleft nasal abnormalities over time is highlighted by the fact that these follow-up operations frequently address problems that result from modifications in the nasal framework or changes in the facial skeleton [46,51].

Surgical techniques

A variety of surgical methods have been developed and used to address severe nasal deformities caused by cleft lip and/or palate (CLP), which can have a substantial impact on a patient's appearance [11]. However, one the fundamental philosophies is the one developed by Jean Delaire. He played important role in cleft rhinoplasty, emphasizing functional and anatomical correction [54]. His approach focused on restoring nasal balance and symmetry by addressing the underlying musculoskeletal deformities [55]. He introduced methods such as early functional cheiloplasty techniques, nasal cartilage remodelling and septal alignment. Along with his colleagues, Delaire also developed combined procedures such as lip-nose correction with Le Fort I osteotomy for secondary deformities [56]. This section outlines the most common surgical techniques used to correct cleft nasal deformities.

Millard's rotation-advancement technique: This technique is one of the most commonly used procedures for repairing cleft lip [34]. This technique focuses on both functional and aesthetic reconstruction of the lip, while also addressing the associated nasal deformities commonly seen in cleft lip patients [50]. The rotation involves rotating the medial portion of the cleft lip to bring it into alignment with the rest of the lip [34]. The goal is to reconstruct the normal cupid's bow and restore symmetry. The lateral segment (the side of the lip affected by the cleft) is advanced and repositioned to close the gap and join with the rotated medial portion, resulting in a more natural-looking lip closure [30]. This technique allows for repositioning of nasal cartilage, improvement of nasal tip and columella and provide nasal base support.

McComb's technique: This method shortens the cleft-side nose by lifting the alar cartilage with its vestibular lining. To liberate the medial and lateral crura, dissection is done in a subcutaneous plane from the upper buccal sulcus as well as via the columella [46]. The dissection is then carried to the tip, dorsum, and nasion from the nostril rim. One or two mattress sutures into the nasal lining at the intercrural angle are used to raise the lower lateral alar cartilages on the cleft side to a symmetrical position, achieving the alar lift columella [52].

Potter technique: This is a well-known method for correcting secondary cleft lip noses that involves releasing nasal structures (alae and muscles). A skin incision is made at the lateral lip segment of the cleft and continues over the nasal vestibule [48]. Vestibular skin incisions are then made along the marginal and intercartilaginous borders to create a V-shaped composite flap made of vestibular skin and alar cartilage, which is then raised with scissors to deglove the alar cartilage at the nasal tip level. The composite flap is then displaced medially, which realigns the cartilaginous structure of the nose. Lastly, transcutaneous stitches with polyglycolic acid sutures via the skin are used to close all incisions in a manner akin to the earlier method [48].

V-Y-Z technique: The V-Y-Z technique utilizes a V-shaped composite flap in conjunction with a lateral Z-plasty [11]. Incisions in the vestibular skin are made along the marginal and intercartilaginous borders surrounding the alar cartilage to create the composite flap. The two limbs of the lateral Z-plasty are positioned at the lateral aspect of the V-shaped flap. Both the composite flap and Z-plasty limbs are carefully incised and elevated using fine scissors. The alar cartilage is then displaced medially to close the vestibular skin through the V-Y plasty, and the lateral flaps are transposed in the Z-plasty configuration. The nasal skin is reshaped with transcutaneous stitches, as done in the other two techniques. The V-Y plasty enables realignment of the alar cartilage and extension of the columella, while the lateral Z-plasty helps prevent scar contracture at the vestibular incision sites [11,53].

Anderl's technique: This approach incorporates the incisions used for cleft lip repair and involves extensive undermining of the nasal skin [53]. It allows for achieving broad mobilization through undermining of the nasal dorsum and supraperiosteal dissection, extending from the vestibule to the infraorbital rim and from the piriform aperture to the maxillary tuberosity. This manoeuvre allows for greater medial displacement of the lateral components during lip and nose repair. The cartilaginous septum is also released from its attachment to the hard palate, realigned, and sutured to the anterior nasal spine [53].

Surgical challenges

Surgeons face a variety of difficulties while performing primary and secondary surgical procedures on patients with cleft nose abnormalities. The timing of the intervention is essential to attaining desired results. Early surgery could improve a child's nasal symmetry at a developmental period that can benefit both function and appearance. However, the continuous development of the face tissues, especially the nasal framework, which keeps changing long into adolescence, may be hampered by early intervention. Early surgery could disrupt healthy facial growth and have unfavourable long-term repercussions. For this reason, surgeons must weigh the benefits of early repair against the risk of growth issues when determining when to operate [17,20].

Preserving nasal function is a major obstacle in cleft nasal surgery. Even while aesthetic enhancements are frequently the main goal, maintaining or regaining nasal airway patency is just as crucial. While in many cases, cleft patients suffer from severe septal deviations or malformations that can obstruct the nasal airway, complicating efforts to improve the nose's appearance while ensuring it functions properly [20]. In severe cases, when the underlying anatomy may be seriously affected, striking a balance between maintaining adequate breathing function and improving the aesthetics of the nose can be very difficult. Long-term respiratory problems may arise from inadequate airway function, Therefore, functional objectives must always be considered alongside aesthetic goals in addition to aesthetic goals [20,52].

Moreover, additional complexity in cleft nose reconstruction arises from scar tissue from earlier procedures, especially in secondary cases. Frequently, further procedures are needed to improve the first results or to address changes that arise as the patient matures. However, the presence of scar tissue from previous surgeries may increase the difficulty of more involved operations [34]. Scar tissue can cause contracture, limit tissue mobility, and obscure critical anatomical landmarks, increasing the risk of complications such as poor wound healing, infection, or unsatisfactory cosmetic results. The surgeon must navigate these challenges carefully, often requiring advanced techniques to manage scar tissue and optimize the chances of a favourable outcome [51].

For long-term stability following cleft nose surgery, sufficient skeletal support is essential in addition to scar tissue management. To maintain the nose's shape and functionality over time, many cleft patients do not have strong underlying support systems [11]. This should be addressed by providing structural reinforcement, often using cartilage grafts or other techniques to create a stable foundation that can withstand the forces of growth and healing. Surgeons must address this by providing structural reinforcement, often using cartilage grafts or other techniques to create a stable foundation that can withstand the forces of growth and healing [16].

Achieving symmetry is probably the biggest challenge in cleft nasal surgery. Even with finely planned surgery, exact symmetry is frequently unattainable because of the inherent abnormalities associated with cleft disorders. It is challenging to achieve a completely balanced nasal appearance because of the intricacy of the cleft deformity and each patient's distinct anatomy. Uneven results can be caused by a variety of factors, including scarring variability, asymmetrical growth patterns, and the extent of tissue insufficiency. Even in the best surgical hands, some degree of asymmetry is often inevitable, despite the goal of creating as much symmetry as possible. Notwithstanding these difficulties, improvements in surgical methods and a better understanding of cleft anatomy keep leading to better results, which eventually enable patients attain more aesthetically beautiful and functional ends [41,43].

Conclusion

Nasal deformities associated with CLP pose significant challenges due to the complex anatomy and functional limitations they entail. Effective management requires a thorough understanding of these deformities, careful pre-surgical planning, and precise surgical intervention. Postoperative care is essential for optimal recovery and long-term success, with ongoing monitoring necessary to address any issues that arise over time.

The narrative review's limitations are acknowledged by the authors. Many of the included trials lacked a cohesive strategy for treatment. Moreover, case reports could reflect the preferences of specific surgeons rather than providing a comprehensive comparison as would be provided by systematic reviews or meta-analyses. We suggest conducting further research, including meta-analyses, in order to provide guidelines for addressing nasal abnormalities in orofacial clefts.

Funding

This article received no specific funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary material. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Author contribution statement

Sultan Ghazal and Wala Ahmed contributed to study design and development, preparation of artwork, and manuscript drafting and editing.

Kamis Gaballah supervised the project, provided continuous guidance, and performed the final edits and manuscript review.

Lujayn Abu Taha, Nuha Altrabulsi, and Layan AlNatsheh conducted the literature search, data collection, and analysis.

All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Sabbagh HJ, Mossey PA, Innes NP. Prevalence of orofacial clefts in Saudi Arabia and neighboring countries: A systematic review. Saudi Dent J 2012 Jan;24(1): 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sdentj.2011.11.001. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhodon L, Prasad V, Aravindhan A, Zaidi SjA. Prosthetic rehabilitation of patients with cleft lip and palate. J Cleft Lip Palate Craniofac Anomal 2022; 9 (2): 189. https://doi.org/10.4103/jclpca.jclpca_6_22. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman G, Wasserzug O. Acquired nasal deformity and reconstruction. In: Springer eBooks. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer 2013. pp 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-23499-6_467. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrich RJ, Ahmad J. Rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011; 128 (2): 49e–73e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821e7191. [Google Scholar]

- Hetzler L, Givens V, Sykes J. The tripod concept of the upper nasal third. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2019; 21 (6): 498–503. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0884. [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Xu X, Wan T, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Wu Y, Liang Y. Correction of narrow nostril deformity secondary to cleft lip: indications for different surgical methods and a retrospective study. Front Pediatr. 2023; 11 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2023.1156275. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CJ, Slowikowski L, Flores RL, Schuster LA. Anatomy of cleft lip and palate. In: 2022. p. 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119778387.ch5. [Google Scholar]

- Arosarena OA. Cleft lip and palate. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2007; 40 (1): 27–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2006.10.011. [Google Scholar]

- Shih CW, Sykes JM. Correction of the cleft-lip nasal deformity. Facial Plast Surg. 2002; 18 (4): 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2002-36493. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DM. Unilateral cleft lip repair: an anatomical subunit approximation technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005; 116 (1): 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000169693.87591.9b. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrich RJ, Benkler M, Avashia YJ, Savetsky IL. Secondary rhinoplasty for unilateral cleft nasal deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021 Jul;148(1): 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000008124. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanthaya K, Panneerselvam E, Manuel S, Kumar VV, Rai A, editors. Oral and maxillofacial surgery for the clinician. Singapore: Springer Singapore 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1346-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kim YC, Hong DW, Oh TS. Comparison of cleft lip nasal deformities between lesser-form and incomplete cleft lips: Implication for primary rhinoplasty. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022; 105566562211052. https://doi.org/10.1177/10556656221105204. [Google Scholar]

- Joos U, Markus AF, Schuon R. Functional cleft palate surgery. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2023 Mar 1;13(2):290–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobcr.2023.02.003. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher MD, Fisher DM, Marcus JR. Correction of the cleft nasal deformity. Clin Plast Surg. 2014; 41 (2): 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2014.01.002. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas T, Gupta P, Kumar S, Gupta R, Gupta T, Singh HP. Cleft of lip and palate: a review. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2020 Jun 30;9(6): 2621–2625. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_472_20. [Google Scholar]

- Guilleminault C, Sullivan S. Towards restoration of continuous nasal breathing as the ultimate treatment goal in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Enliven: Pediatr Neonatal Biol. 2014; 1(01). https://www.enlivenarchive.org/articles/towards-restoration-of-continuous-nasal-breathing-as-the-ultimate-treatment-goal-in-pediatric-obstructive-sleep-apnea.html. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson Y. Mouth breathing: adverse effects on facial growth, health, academics, and behavior. Gen Dent. 2010; 58 (1): 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zuhaib M, Bonanthaya K, Parmar R, Shetty PN, Sharma P. Presurgical nasoalveolar moulding in unilateral cleft lip and palate. Indian J Plast Surg. 2016 Jan-Apr;49(1): 42–52. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0358.182235. [Google Scholar]

- Paradowska-Stolarz A, Mikulewicz M, Duś-Ilnicka I. Current concepts and challenges in the treatment of cleft lip and palate patients—a comprehensive review. J Pers Med. 2022; 12 (12): 2089. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12122089. [Google Scholar]

- Koželj V. Experience with presurgical nasal molding in infants with cleft lip and nose deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007 Sep;120(3): 738–745. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000270847.12427.25. [Google Scholar]

- Saad MS, Fata M, Farouk A, et al. Early progressive maxillary changes with nasoalveolar molding: randomized controlled clinical trial. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2020; 5 (4): 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/2380084419887336. [Google Scholar]

- Carter CB, Gallardo FF, Colburn HE, Schlieder DW. Novel digital workflow for nasoalveolar molding and postoperative nasal stent for infants with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2022; 60 (9): 1176–1181. https://doi.org/10.1177/10556656221095393. [Google Scholar]

- Lautner N, Raith S, Ooms M, Peters F, Hölzle F, Modabber A. Three-dimensional evaluation of the effect of nasoalveolar molding on the volume of the alveolar gap in unilateral clefts. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2019; 48 (2): 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2019.12.012. [Google Scholar]

- Ahsanuddin S, Ahmed M, Slowikowski L, Heitzler J. Recent advances in nasoalveolar molding therapy using 3D technology. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2022; 15 (4): 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211044622. [Google Scholar]

- Chou PY, Hallac RR, Ajiwe T, Xie XJ, Liao YF, Kane AA, Park YJ. The role of nasoalveolar molding: A 3D prospective analysis. Sci Rep. 2017; 7(1).https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10435-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dunworth K, Porras Fimbres D, Trotta R, et al. Systematic review and critical appraisal of the evidence base for nasoalveolar molding (NAM). Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2024; 61 (4): 654–677. https://doi.org/10.1177/10556656221136325. [Google Scholar]

- Zelko I, Zielinski E, Santiago CN, Alkureishi LW, Purnell CA. Primary cleft rhinoplasty: a systematic review of results, growth restriction, and avoiding secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023 Mar;151(3):452e–62e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000009924. [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg DJ. Dental and prosthodontic care for patients with cleft or craniofacial conditions. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2000 Nov;37(6): 534–7. https://doi.org/10.1597/1545-1569_2000_037_0534_dapcfp_2.0.co_2. [Google Scholar]

- Broll D, de Souza TV, Nobrega E, Luz CL, Repeke CE, da Silva LC, Garib DG, Ozawa TO. Columella elongation surgery outcome in complete bilateral cleft lip and palate. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019 Mar 25;7(3):e2147. https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000002147. [Google Scholar]

- Burgaz MA, Cakan DG, Yılmaz RB. Three-dimensional evaluation of alveolar changes induced by nasoalveolar molding in infants with unilateral cleft lip and palate: a case-control study. Korean J Orthod. 2019; 49 (5): 286. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod.2019.49.5.286. [Google Scholar]

- Rawashdeh MA, Telfah H. Secondary alveolar bone grafting: the dilemma of donor site selection and morbidity. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008; 46 (8): 665–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.07.184. [Google Scholar]

- Saito T, Lo CC, Tu JC-Y., Hattori Y, Chou P-Y., Lo LJ. Secondary bilateral cleft rhinoplasty: achieving an aesthetic result. Aesthet Surg J. 2024 Feb 5;44(6).https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjae019. [Google Scholar]

- Rawashdeh MA. Morbidity of iliac crest donor site following open bone harvesting in cleft lip and palate patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 Mar;37(3): 223–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2007.11.009. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S, Mølsted K. Long-term outcome of secondary alveolar bone grafting in cleft lip and palate patients: a 10-year follow-up cohort study. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2013; 47 (6): 503–508. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23621098/. [Google Scholar]

- Brudnicki A, Petrova T, Dubovska I, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM, Ren Y, Fudalej PS. Alveolar bone grafting in unilateral cleft lip and palate: impact of timing on palatal shape. J Clin Med. 2023; 12 (24): 7519. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12247519. [Google Scholar]

- Feichtinger M, Mossböck R, Kärcher H. Assessment of bone resorption after secondary alveolar bone grafting using three-dimensional computed tomography: a three-year study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2007; 44 (2): 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1597/06-047.1. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy AS, Lehman JD. Secondary alveolar bone grafting: an outcome analysis. 2006; 14 (3): 172–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/229255030601400307. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg J, Levring Jäghagen E, Sjöström M. Outcome after secondary alveolar bone grafting among patients with cleft lip and palate at 16 years of age: a retrospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2021; 132 (3): 281–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2021.04.057. [Google Scholar]

- Celie KB, Wright MA, Ascherman JA. Primary cleft rhinoplasty: long-term outcomes of a single technique used over 2 decades. Ann Plast Surg. 2021 Jul;87 (1s). https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002804. [Google Scholar]

- Wadde K, Chowdhar A, Venkatakrishnan L, Ghodake M, Sachdev SS, Chhapane A. Protocols in the management of cleft lip and palate: a systematic review. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2023 Apr;124(2):101338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jormas.2022.11.014. [Google Scholar]

- Dallaserra M, Pantoja T, Salazar J, Araya I, Yanine N, Villanueva J. Effectiveness of pre-surgical orthopedics on patients with cleft lip and palate: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022; 123 (5): e506–e520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jormas.2022.02.004. [Google Scholar]

- Murali SP, Denadai R, Sato N, Lin H-H., Hsiao J, Pai BCJ, Chou P-Y., Lo L-J. Long-term outcome of primary rhinoplasty with overcorrection in patients with unilateral cleft lip: avoiding intermediate rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023 Mar;151(3):441e–451e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000009923. [Google Scholar]

- Stal S, Brown RA, Higuera S, Hollier LH, Byrd HS, Cutting CB, Mulliken JB. Fifty years of the Millard rotation-advancement: looking back and moving forward. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 123 (4): 1364–1377. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0b013e31819e26a5. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Freitas R, Bertoco Alves P, Shimizu GK, Schuchovski JF, Lopes MAC, Maluf I, Forte AJV, Alonso N, Shin J. Beyond fifty years of Millard's rotation-advancement technique in cleft lip closure: Are there many ‘Millards’? Plast Surg Int. 2012; 2012: 731029. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/731029. [Google Scholar]

- Rossell-Perry P. Primary cleft rhinoplasty: surgical outcomes and complications using three techniques for unilateral cleft lip nose repair. J Craniofac Surg. 2019; 31 (6): 1521–1525. https://doi.org/10.1097/scs.0000000000006043. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein SW, Monroe CW, Kernahan DA, Jacobson BN, Griffith BH, Bauer BS. The case for early bone grafting in cleft lip and cleft palate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982; 70 (3): 297–307. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198209000-00001. [Google Scholar]

- Chopan M, Sayadi L, Laub DR. Surgical techniques for treatment of unilateral cleft lip. In: Designing strategies for cleft lip and palate care. 2017. https://doi.org/10.5772/67124. [Google Scholar]

- Dissaux C, Bodin F, Grollemund B, Bridonneau T, Kauffmann I, Mattern JF, Bruant-Rodier C. Evaluation of success of alveolar cleft bone graft performed at 5 years versus 10 years of age. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016; 44 (1): 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2015.09.003. [Google Scholar]

- Agochukwu-Nwubah N, Boustany A, Vasconez HC. Cleft rhinoplasty study and evolution. J Craniofac Surg. 2019 Jul;30(5): 1430–1434. https://doi.org/10.1097/scs.0000000000005304. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshal SG, Solis RN, Tollefson TT. Controversies in cleft rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2020 Feb;36(1): 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1701477. [Google Scholar]

- Anderl H, Hussl H, Ninkovic M. Primary simultaneous lip and nose repair in the unilateral cleft lip and palate. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008; 121 (3): 959–970. [Google Scholar]

- Tse RW, Mercan E, Fisher DM, Hopper RA, Birgfeld CB, Gruss JS. Unilateral cleft lip nasal deformity: Foundation-based approach to primary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Nov;144(5): 1138–1149. https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000006182. [Google Scholar]

- Delaire J, Talmant JC, Billet J. Evolution of cheiloplasty techniques for cleft lip and palate (and study of some complementary procedures). Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1972;73(5): 337–357. JT French. PMID: 4512518. [Google Scholar]

- Talmant JC. Nasal defects associated with unilateral cleft lip: accurate diagnosis and management. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1993; 27 (3): 183–191. https://doi.org/10.3109/02844319309078110. PMID: 8272769. [Google Scholar]

- Schendel SA, Delaire J. Functional musculoskeletal correction of secondary unilateral cleft lip: combined lip-nose correction and Le Fort I osteotomy. J Maxillofac Surg. 1981; 9: 108–116. [Google Scholar]

Cite this article as: Ghazal S, Ahmed W, Abu Taha L, Gaballah K, Altrabulsi N, AlNatsheh L. 2025. Nasal deformities in cleft lip and palate: an update for dental professionals. J Oral Med Oral Surg. 31, 16: https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2025017

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 A) The right and left lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilage act as two legs of a tripod supporting, the nasal tip, while the medial crura form the third leg. B) Note the discontinuity in the orbicularis oris muscle and the lip length discrepancy. C) Slumping and lateral displacement of the alar dome, as well as displacement of the nasal septum. D) Note the flat nasal tip, short columella, and lateral displacement of the alar cartilage. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 A) Digital impression-taking for fabrication of PSIO. B and C) Acrylic plate with a nasal stent extending from the vestibular aspect. B is for unilateral cleft, and C for bilateral cleft deformities. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 A) Nasal Conformer. B) Note the widened alar base post-primary lip and nose repair. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Reflection of the full mucoperiosteal flap, exposure of alveolar bone and ABG in the cleft defect. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.