| Issue |

J Oral Med Oral Surg

Volume 27, Number 2, 2021

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | 25 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/mbcb/2020066 | |

| Published online | 17 February 2021 | |

Educational Article

Central Odontogenic Fibroma: characteristics and management

Department of Oral Surgery, CHU Hôtel-Dieu, Nantes, France

* Correspondence: alexandra.cloitre@univ-nantes.fr

Received:

15

June

2020

Accepted:

5

November

2020

Introduction: Central Odontogenic Fibroma (COF) is a rare benign odontogenic tumour of the jaws. Until its recent change in classification by the WHO in 2017, this entity has gone without an agreed upon definition for many years. For this reason, COF would remain largely unknown to practitioners. Corpus: The pedagogical objectives of this article are, through a systematic review of the literature using the PRISMA methodology, to list the epidemiological, aetiological, clinical, radiological, histological, therapeutic and prognostic characteristics of COF. All the data collected made it possible to establish a COF management summary for practitioners in order to optimize it. Conclusion: Based on the 135 cases listed, it appears that surgical enucleation is the treatment of choice for COF. The recurrence rate is low and malignant transformation has never been reported. However, regular clinical and radiological follow-up of patients over several years seems to be a justified precaution.

Key words: Fibroma / odontogenic tumors / jaw neoplasm

© The authors, 2021

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Central Odontogenic Fibroma (COF) is a rare benign odontogenic tumour of mesenchymal origin [1]. This tumour consists of mature connective tissue in which islands or strands of inactive-looking odontogenic epithelium can be found with or without evidence of calcification. Described for the first time by the WHO in 1971, COF has not had a consensual definition for years and its classification has recently undergone changes. Since 2017, the WHO now distinguishes the lesion according to its location (central or peripheral) and no longer on the basis of histological criteria [1]. Simple and complex histological subtypes (poor and rich in inactive-looking odontogenic epithelium, respectively) have thus been removed from this classification, without any justification.

Very few studies have been published on COF, and those that have consist mainly of case reports or small series from which it is difficult to draw conclusions. In more, only one systematic review without histological variant has been carried out, but it does not specify the articles used for their statistical analysis [2]. Given its rarity, the evolving nature of its definition and classification, COF is relatively unknown to practitioners. Based on a systematic review of the literature using the PRISMA methodology, we collected and analysed the various cases of COF in order to optimize its management. The educational objectives are:

-

To update the epidemiological data on COF

-

To clarify its aetiology

-

To describe its clinical, radiological and histological characteristics

-

To discuss its possible differential diagnoses

-

To determine its treatment of choice

-

To assess its prognosis and to estimate the follow-up duration required after treatment.

Corpus

Materials and method of the systematic review

A systematic review of the literature was performed according to the PRISMA methodology. An electronic search was conducted up until April 15, 2019 in the Scopus and PubMed databases. The keywords MeSH (“fibroma” and “odontogenic tumors”) were used. The search equation was on Scopus: “KEY (“fibroma”) OR KEY (“Odontogenic tumors”) AND ALL (“central odontogenic fibroma”) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“re”))”, and on PubMed: “(“Fibroma” [Mesh]) AND (“Odontogenic Tumors” [Mesh]) AND ((Review[ptyp] OR Case Reports[ptyp])”. No restrictions on the date of publication have been imposed. This main search was supplemented by a manual search in the bibliographic references of the selected articles. After removing the duplicates, the identified articles were selected based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Criteria for inclusion:

-

Cases involving humans;

-

Studies respecting the current WHO definition (2017) [1];

-

Studies reporting COF case(s) mentioning information on at least age, gender, location and/or radiological features, histological diagnosis and/or surgical technique;

-

Articles in English or French.

Criteria for exclusion:

-

Studies with uncertain diagnosis;

-

Studies without mention of location (central or peripheral);

-

Purely immunohistochemical studies on benign odontogenic tumours;

-

Studies on histological variants of COF: giant cell COF, amyloid-like protein deposition COF, granular cell odontogenic tumours.

The article selection process is described in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1). 81 articles (7 retrospective studies and 74 case reports) were included bringing the total number of COF cases listed to 135. Data from these cases were extracted using a dedicated grid. This data concerned (1) age and sex, (2) clinical features, (3) radiological features, (4) histological features, (5) treatments performed, (6) follow-up duration, (7) possible recurrence and malignant transformation. Where the histological or radiological characteristics of COF were not fully described, two authors independently evaluated the figures to remedy it. The included publications had a low level of scientific evidence (level 4) according to the evaluation criteria of the National Agency for Accreditation and Evaluation in Health (ANAES).

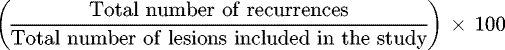

Based on the data from the included articles, the COF recurrence rate was calculated as follows:

|

Fig. 1 PRISMA flowchart of the systematic literature review. |

Responses to the educational objectives

Epidemiology

COF is considered by the WHO to be a rare tumour but no epidemiological data are shown [1]. It represented 1.5% of central odontogenic tumours (16 cases out of 1088 biopsied tumours) [3]. This was probably an overestimate since histological variants of COF (such as ossifying odontogenic fibroma) that are no longer recognized by the WHO have been accounted for. Our systematic literature review identified 135 cases of COF. This was 41 cases less than the 176 cases listed by Correa Pontes et al. in their systematic review but comparison with our data was impossible since these authors did not reference all the cases included [2]. Based on the 135 cases we identified, COF occurred in a wide age range, from 3 to 80 years, with an average age of 30 years (Fig. 2). A predominance was observed between the second and third decade of life regardless of gender. The male/female sex ratio was 0.8.

|

Fig. 2 Distribution of central odontogenic fibroma by age and sex. |

Aetiology

The aetiology of COF remains unknown. According to one hypothesis that was taken up by the WHO in 2005, COF would derive from the dental follicle for simple histological types and from the periodontal ligament for complex types [4]. These 2 potential origins are no longer listed in the current WHO classification (2017) [1]. In addition, one case of COF associated with tuberous sclerosis complex [5] and one case associated with Gorlin syndrome [6] have been described without a proven causal link.

Clinical features

COF was located more frequently in the mandible (53.3% of cases) than in the maxilla (46.7% of cases) (Fig. 3A). In the mandible, the most affected area was the posterior molar sector (58.3% of cases), followed by the premolar sector (38.9% of cases) and the ramus (26.4% of cases) (Fig. 3B). In the maxilla, the premolar region was most frequently affected (63.4% of cases), followed by the incisor − canine sector (49.2% of cases) and finally the posterior molar sector (19% of cases).

COF was most often made apparent by clinical signs in 47.4% of cases. These signs might be physical in 41% of cases (facial asymmetry and/or intraoral swelling in 34.1% of cases [7–29], dental mobility in 2.2% [30–32], trismus in 0.7% [33], tooth displacement in 0.7% [34], or delayed eruption in 0.7% [35]). These clinical signs might also be functional with pain in 6.7% of cases [7,12,32,36–40]. COF might also be discovered incidentally on standard radiograph in 23% of cases [33,36–38, 41–56].

The extraoral clinical manifestations of COF were infrequent and non-specific (Tab. I). They were absent in 74.8% of cases [11,24,36,47,50,57–65]. Facial asymmetry was observed in 23.7% of cases [5,7–9,12–18,20–22,25,26,31,33,40,58,60,63,66–74]. This facial asymmetry was isolated in 20.7% of cases and associated with other extraoral clinical signs in 3% of cases (lymphadenopathy in 1.5% of cases [12,66], trismus in 0.7% [33] and paraesthesia in 0.7% [73]).

On intraoral examination, COF mostly manifested as mucosal lesions of variable relief (75.6% of cases) (Tab. II). A slowly progressive swelling was the most frequently found feature (57.8% of cases) [5,7–27,29,31–33,36–38,40,42,47,50,52,57–60,62–78]. Vestibular swelling and palatal depression could also be associated in 2.2% of cases [38,42]. In case of palatal localization, mucosal depression (8.9% of cases) [28,38,42,50,52,54,56,79] and mucosal perforation or fistula (3.7% of cases) [38,50,54,56,79] might be observed. An erythematous plaque of the oral mucosa was reported in 3% of cases [10,27,66,69]. More rarely, COF presented itself in dental signs, as they were found in only 18.4% of cases. Thereby, delayed tooth eruption was noted in 9.6% of cases [12,16,20,35,44,46,48,52,57,58,66,80], mobility in 8.1% of cases [10,12,30–32,38,42,79,81,82] and exceptionally pulp necrosis in 0.7% of cases [50].

|

Fig. 3 Distribution of locations of central odontogenic fibroma. (A) According to the involved jaw (maxilla or mandible). (B) According to the site involved within the maxilla or mandible. The sum of the theses percentages is higher than 100% because a lesion can be located in several sites. This figure was made using Servier Medical Art templates − https://smart.servier.com. |

Extraoral features of central odontogenic fibroma.

Intraoral clinical features of central odontogenic fibroma.

Radiological features

The radiological aspect of COF was not pathognomonic (Tab. III). On panoramic radiographs, the tumour usually presented itself as a single homogeneous radiolucent lesion, sometimes unilobular (54.1% of cases) [6,8,12,19–24,26,28,30,32–36,38,42–49,51–55,59,61,62,64,67,69–71,74,75,77–79, 81–85] sometimes multilobular (23.7% of cases) [5,7,11,13,15–18,25,27,29,31,36,38,39,41,42,50,56–58,68,73,76,77,83]. Mixed images with radiopacities corresponding to irregular and disseminated calcifications were described with a unilobular appearance in 6.7% of cases [20,36,40,57,60,63,65,72,80] and a multilobular appearance in 4.4% of cases [15,36,38,39,56,69]. Radiopaque lesion has never been reported in the literature.

The lesion was generally well delineated with a peripheral border of osteocondensation present in 37% of cases [5,6,8,9,17,20,23–26,28–40,43,44,46,48–51,55,56,58–62,65–67,69–72,74,75,77–80,82,83] and absent in 21.5% of cases [7,10,11,16,18,22,27,32,34,36,38,41,43,52–54,56,57,59,75–77,81,82,85]. A blurred contour was observed in 8.9% of cases [12,13,15,19,36,63,64,68,73,77,84], and even periosteal reaction in 1.5% of cases [13,77]. The size of the lesion could vary from 3 to 60 mm in its largest dimension, with a mean of 25.6 mm. According to the WHO, small-sized lesions tend to be unilobular, while large-sized lesions are multilobular [1]. Our data did not confirm this statement since the measurement of unilobular and multilobular lesions were extremely close (mean of 25 and 26 mm respectively).

As for the surrounding anatomical elements, COF tended to push them without invading them. Teeth were displaced in 40% of cases and external root resorptions were observed in 24.4% of cases (Tab. IV). The association of COF with impacted tooth was relatively common (28.9% of cases). It might be canine or molar [5,12,15,16,18,20,25,35–37,40,43,44,46,48,50,51,57–60,62,66,67,69,72,77,78,80,83]. Finally, cortical bone perforations were reported in 16.3% of cases [5,10,12,13,16,18, 22,28, 33,43,47,50,54,56,67,69,71,72,77,81,83,85].

Radiological features of central odontogenic fibroma.

Radiological features of the anatomical elements surrounding central odontogenic fibroma.

Histological features

The histological subtype of COF was indeterminate in 37% of cases. Otherwise the distribution between the complex type and the simple type appeared to be almost equivalent with 34.1% of cases [8,15,21,23,26,28–30,34–37,39,40,46,47,50–54,56,57,60,61,63,65,70–74,76,78,80,82,85] and 28.9% of cases respectively [6,7,11–14,17,18,20,22,24,25,27,31,32, 36,37,43,45,48,49,55,58,59,62,64,66–69,75,79,81,83,84]. Examination of the clinical and radiological features did not reveal any characteristics specific to a COF subtype. The simple and complex subtype separation, which has been removed from the latest version of the WHO classification, did not appear to be of clinical interest since the behaviour of these two lesions seemed to be identical.

Differential diagnosis

When COF was associated with an impacted tooth, differential diagnoses included dentigerous cyst, desmoplastic fibroma, ameloblastoma, odontogenic keratocyst, and ameloblastic fibroma [5,12,15,16,18,25,36,37,40,44,46,51,57–60,62,66,67,69,72,77,78,83]. On the contrary, when COF was not associated with a tooth, a wide range of odontogenic tumours could be evoked such as odontogenic myxoma [9,10,14,21,23,24,29,30,34,54,59,65,67,68,76,77]. Sclerosing odontogenic carcinoma should also be mentioned because of its histological similarity [1]. In all cases, the diagnosis of COF could only be made after cross-checking the clinical, radiological and histological data [1].

Therapeutic

The treatment of choice for COF was surgical enucleation, which was performed in 2/3 of cases (65.9% of cases) [6,8,10,11,16–18,21–24,26–30,32,36–38,40–42,45,46,49,51, 54–56,58–60,62,64,66–68,73–76,78,79,81–83] (Fig. 4). Other conservative surgical approaches were less frequently practised: curettage of the lesion (14.1% of cases) [7,12,19,43, 47,48,50,52,65,69,72,80,84] or even non-interruptive resection (1.5% of cases) [15,85]. Enucleation is the process by which the entire cystic lesion is removed in one surgical piece [86]. In contrast, during excisional curettage the tumor is fragmented in several pieces. Non-conservative treatment like interruptive mandibulectomy was performed in 4.4% of cases [5,13,14,33,57,70]. Finally, therapeutic abstention was decided in only one case because of the patient's advanced age, the extent of the lesion and its non-aggressive nature (0.7%) [50]. In addition to COF treatment, tooth extractions were performed in 19.3% of cases to facilitate access to the lesion or because the adjacent teeth were not retainable due to external root resorptions [6,7,10,14,25, 29,30,32,37,44,46,50,51,53,56,57, 66,68,71,78,79,82,83,85]. More rarely, in 3% of cases, endodontic treatments were performed [6,23,54,83], of which 3/4 were associated with apical surgery (2.2% of cases) [6,54,83]).

|

Fig. 4 Therapeutic approaches used in the treatment of central odontogenic fibroma. |

Follow-up and prognosis

The mean duration of patient follow-up after COF treatment was 35 months (SD 39.1, range 1 month to 180 months) for the 86 cases reporting this duration [6,7,9–14,16–20,22,24,27–30,32–34,36,38,42–44,46–59,62,65,66,68–74,76,78,81–83,85].

COF is considered by the WHO to be a non-aggressive and non-recurrent tumour [1]. While it was difficult to determine the aggressiveness of COF based on literature data, recurrence was quantifiable. Four cases of recurrent COF were reported [9,19,43,73]. The recurrence rate of COF was 6% and its annual recurrence rate was 1.4%. For these calculations, only data from 67 patients with a minimum follow-up of 12-months after surgical treatment was considered (estimated duration of effective mucosal and bone healing) [6,7,9,10,12,14,16–19,22,27–29,32–34,36,38,42–44,46,48–52,55–59,62,65,66, 69,70,72,73,78,81,83,85]. This recurrence rate of 6% was lower than the rate of 10% suggested by Correa Pontes et al. [2]. This last rate was calculated based on 5 cases of recurrent COF out of a total of 50 cases that indicated the presence (or absence) of recurrence. The authors did not impose a minimum duration of follow-up after treatment for the selection of these 50 cases, which would have allowed to distinguish a delay in healing from a recurrence of the lesion. Moreover, the cases selected to establish this rate were not referenced.

No prognostic factors could be identified from the literature because the number of recurrent cases seems too limited to allow a reliable calculation of the recurrence rate of COF for each suspected risk factor.

Recurrences were diagnosed between 16 and 108 months after treatment (mean = 52 months, SD = 42). It should be noted that although the longest recurrence was diagnosed at 108 months (i.e. 9 years) after the procedure, a radiological examination at 48 months had already detected a radiolucent lesion at the same site as the COF. Earlier diagnosis would have been possible if additional investigations had been undertaken at this time. To estimate the minimum duration of follow-up for a COF after treatment, we took into account the longest time between treatment and the onset of signs of recurrence of the lesion, which was 60 months [19].

Nonetheless, given the lack of regular follow-up of the patient concerned, this is probably a high estimate. Regular long-term clinical and radiological follow-up seems to be necessary to detect signs of potential recurrence. Surgical management of COF recurrences has not been specified for 3 of the 4 cases listed [9,19,43]. In one case an interruptive hemimandibulectomy was performed [73]. Finally, malignant transformation of COF has never been reported in the literature.

An illustrated pedagogical summary of the management of COF, based on the results of this systematic literature review, is proposed to guide practitioners (Fig. 5).

|

Fig. 5 Pedagogical summary of the management of a central odontogenic fibroma. |

Conclusion

COF is a rare benign tumour that predominantly affects 20–30-year-olds and the mandible. The lesion most often manifests as a firm and painless vestibular swelling. The radiological signs are not pathognomonic. The lesion is mostly radiolucent, unilobular with well-defined limits. It tends to push the surrounding structures without invading them. It is frequently associated with an impacted tooth. In rare cases, it can lead to external root resorptions and cortical bone perforations. Diagnosis is based on the convergence of clinical, radiological and histological data. Surgical enucleation is the treatment of choice for COF with a low recurrence rate. Malignant transformation has never been reported in the literature. However, regular clinical and radiological follow-up of the patient over several years seems to be a justified precaution.

Conflicts of interests

Prof. Philippe Lesclous is editor-in-chief of JOMOS review.

References

- El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, éditeurs. WHO classification of head and neck tumours. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer 2017. 347 p. [Google Scholar]

- Correa Pontes FS, Lacerda de Souza L, Paula de Paula L, de Melo Galvão Neto E, Silva Gonçalves PF, Rebelo Pontes HA. Central odontogenic fibroma: an updated systematic review of cases reported in the literature with emphasis on recurrence influencing factors. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2018;46:1753–1757. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of central odontogenic tumours: a study of 1,088 cases from Northern California and comparison to studies from other parts of the world. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;64:1343–1352. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes L. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours: Lyon, France, July 16–19, 2003. Reprinted. Lyon: IARC Press 2007. 430 p. [Google Scholar]

- Swarnkar A, Jungreis CA, Peel RL. Central odontogenic fibroma and intracranial aneurysm associated with tuberous sclerosis. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:66–69. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada Y, Kawasaki Y, Tayama M, Kindaichi J, Maruoka Y. A case of central odontogenic fibroma of the mandible in a nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patient. Oral Sci Int. 2018;15:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura P, Sutter W, Meier M, Berger S, Turhani D. Large mandibular central odontogenic fibroma documented over 20 years: a case report. Int. J Surg Case Rep. 2017;41:481–488. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodner L. Central odontogenic fibroma. A case report. International J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;22:166–167. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heimdal A, Isacsson G, Nilsson L. Recurrent central odontogenic fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;50:140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra V, Chhabra A. Central odontogenic fibroma of the mandible. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3:230. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskala I, Kalyvas D, Kolokoudias M, Vlachodimitropoulos D, Alexandridis C. Central odontogenic fibroma of the mandible: a case report. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:457–461. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicconetti A, Bartoli A, Tallarico M, Maggiani F, Santaniello S. Central odontogenic fibroma interesting the maxillary sinus. A case report and literature survey. Minerva Stomatol. 2006;55:229–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anbiaee N, Ebrahimnejad H, Sanaei A. Central odontogenic fibroma (simple type) in a four-year-old boy: atypical cone-beam computed tomographic appearance with periosteal reaction. Imaging Sci Dent. 2015;45:109–115. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Ohba S, Yoshimura H, Katase N, Imamura Y, Ueno T, et al. Epithelium-poor type central odontogenic fibroma: an immunohistological study and review of the literature. J Hard Tissue Biol. 2013;22:273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Murgod S, Girish HC, Savita JK, Varsha VK. Concurrent central odontogenic fibroma and dentigerous cyst in the maxilla: a rare case report. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2017;21:149–153. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harti K, Oujilal A, Wafaa EW. Central odontogenic fibroma of the maxilla. Indian J Dent. 2015;6:217. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi SK, Rahpeyma A. Central odontogenic fibroma. Iran J Pathol. 2013;8:131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Nah K-S. Central odontogenic fibroma: a case report. Imaging Sci Dent. 2011;41:85–88. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo AR, Santos T de S, do Amaral MF, Albuquerque D de P, Andrade ES de S, Pereira ED. Recurrence of central odontogenic fibroma: a rare case. Gen Dent. 2011;59:e78–e81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayesha RT, Pachipulusu B, Govindaraju P, Ravindra S. Odontogenic fibroma associated with an impacted tooth. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018;12:ZD06–ZD08. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekar C, Sen S, Narayanaswamy V, Radhakrishnan R. A curious case of central odontogenic fibroma: a novel perspective. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2018;22:S16–S19. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covani U, Crespi R, Perrini N, Barone A. Central odontogenic fibroma: a case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10:E154–E157. [Google Scholar]

- Koszowski R, Śmieszek-Wilczewska J, Stęplewska K. Odontogenic fibroma − a case report. Cent Eur J Med. 2014;9:250–253. [Google Scholar]

- De Matos FR, De Moraes M, Neto AC, Miguel MCDC, Da Silveira EJD. Central odontogenic fibroma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:481–484. [Google Scholar]

- Darche V, Lambert F, Marbaix E, Reychler H. Central odontogenic fibroma: apropos of a case. Acta Stomatol Belg. 1995;92:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramer M, Buonocore P, Krost B. Central odontogenic fibroma-report of a case and review of the literature. Periodontal Clin Investig. 2002;24:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günhan Ö, Finci R, Demiriz M, Gürbüzer B, Gardner DG. A central odontogenic fibroma exhibiting pleomorphic fibroblasts and numerous calcifications. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:42–43. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorge MB, Giunta J, Nersasian RR. A case of a central odontogenic fibroma presenting a differential diagnostic problem. J Mass Dent Soc. 1993;42:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro LS, Martins M, Pacheco JJ, Salazar F, Magalhães J, Vescovi P, et al. Er:YAG Laser assisted treatment of central odontogenic fibroma of the mandible. Case Rep Dent. 2015;2015:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen JH, Blijdorp PA. Central odontogenic fibroma: a case report. J Maxillofac Surg. 1985;13:236–238. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musha A, Yokoo S, Takayama Y, Sato H. Clinicopathological investigation of odontogenic fibroma in tuberous sclerosis complex. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;47:918–922. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishino M, Ishibashi M, Koizumi H, Sato S, Murakami S, Ogawa Y, et al. Central odontogenic fibroma of the maxilla: a case report with immunohistochemical study. Oral Med Pathol. 2009;14:29–32. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi T, Uehara M, Fujita S, Ikeda T, Asahina I. A case of central odontogenic fibroma in a pediatric patient: mandibular reconstruction with parietal bone. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2015;27:361–365. [Google Scholar]

- Soolari A, Khan A. Central odontogenic fibroma of the gingiva: A case report. Open Dent J. 2014;8:280–288. [Google Scholar]

- Lukinmaa P-L, Hietanen J, Anttinen J, Ahonen P. Contiguous enlarged dental follicles with histologic features resembling the WHO type of odontogenic fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990; 70 (3): 313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Hrichi R, Gargallo-Albiol J, Berini-Aytés L, Gay-Escoda C. Central odontogenic fibroma: retrospective study of 8 clinical cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17:e50–e55. [Google Scholar]

- Lin H-P, Chen H-M, Yu C-H, Yang H, Kuo R-C, Kuo Y-S, et al. Odontogenic fibroma: a clinicopathological study of 15 cases. J Formos Med Assoc. 2011;110:27–35. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handlers JP, Abrams AM, Melrose RJ, Danforth R. Central odontogenic fibroma: Clinicopathologic features of 19 cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:46–54. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raubenheimer EJ, Noffke CE. Central odontogenic fibroma-like tumors, hypodontia, and enamel dysplasia: review of the literature and report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;94:74–77. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallow RD, Spatz SS, Zubrow HJ, Kline SN. Odontogenic fibroma with calcification. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;22:564–568. [Google Scholar]

- Jones GM, Eveson JW, Shepherd JP. Central odontogenic fibroma. A report of two controversial cases illustrating diagnostic dilemmas. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;27:406–411. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosqueda-Taylor A, Martínez-Mata G, Carlos-Bregni R, Vargas PA, Toral-Rizo V, Cano-Valdéz AM, et al. Central odontogenic fibroma: new findings and report of a multicentric collaborative study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endodontol. 2011;112:349–358. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Svirsky JA, Abbey LM, Kaugars GE. A clinical review of central odontogenic fibroma: with the addition of three new cases. J Oral Med. 1986;41 (1):51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Lafuente S, Berini-Aytes L, Gay-Escoda C. Central odontogenic fibroma: a review of the literature and report of a new case. Med Oral. 1999;4:422–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshberg A, Dayan D, Horowitz I, Littner MM. The simple central odontogenic fibroma. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1987;15:379–380. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklander S, Martinez R, Deichler J, Esguep A. Bilateral mandibular odontogenic fibroma (WHO type): report of a case with 5-year radiographic follow-up. J Dent Sci. 2011;6:123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JL, Lamster IB, Baden E. Odontogenic fibroma of the complex (WHO) type: report of six cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:666–674. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pippi R, Santoro M, Patini R. The central odontogenic fibroma: how difficult can be making a preliminary diagnosis. J Clin Exp Dent. 2016;8:e223–e225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson JP, Strickland F. Central odontogenic fibroma: case report and review. US Army Med Dep J. 2014;57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl EC, Wolfson SH, Haugen JC. Central odontogenic fibroma: review of literature and report of cases. J Oral Surg. 1981;39:120–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeoka T, Inui M, Okumura K, Nakamura S, Shimizu K, Tagawa T. A central odontogenic fibroma mimicking a dentigerous cyst associated with an impacted mandibular third molar-Immunohistological study and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2013;25:193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap CL, Barker BF. Central odontogenic fibroma of the WHO type. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57:390–394. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WR, Ziskind J. Odontogenic fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1956;9:813–816. [Google Scholar]

- Huey MW, Bramwell JD, Hutter JW, Kratochvil FJ. Central odontogenic fibroma mimicking a lesion of endodontic origin. J Endod. 1995;21:625–627. [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal S, Radhakrishna S, Raj A, Sawhney A. Central odontogenic fibroma. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Ide F, Sakashita H, Kusama K. Ameloblastomatoid, central odontogenic fibroma: an epithelium-rich variant. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:612–614. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cercadillo-Ibarguren I, Berini-Aytés L, Marco-Molina V, Gay-Escoda C. Locally aggressive central odontogenic fibroma associated to an inflammatory cyst: A clinical, histological and immunohistochemical study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35:513–516. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley RK, Wysocki GP, Mintz SM. The central odontogenic fibroma. Clinical and morphologic studies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;40:235–245. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Slootweg PJ, Müller H. Central fibroma of the jaw, odontogenic or desmoplastic. A report of five cases with reference to differential diagnosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;56:61‑70. [Google Scholar]

- Talukder S, Agarwal R, Gupta P, Bs S, Misra D. Central odontogenic fibroma (WHO Type): a case report and review of literature. Kailasam S, éditeur. JIAOMR. juill 2011;23:259‑262. [Google Scholar]

- Thomopoulos G, Markopoulos AK. Central odontogenic fibroma: a case report. Annals of dentistry. 1992;51:12‑13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thankappan P, Chundru N, Amudala R, Yanadi P, Rahamthullah SAKU, et al. Central odontogenic fibroma of simple type. Case Reports in Dentistry. 2014;2014:1‑3. [Google Scholar]

- Veeravarmal V, Madhavan R, Nassar M, Amsaveni R. Central odontogenic fibroma of the maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013;17:319. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariades N. Odontogenic fibroma. International J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986;15:102‑104. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brazão-Silva MT, Fernandes AV, Durighetto-Júnior AF, Cardoso SV, Loyola AM. Central odontogenic fibroma: A case report with long-term follow-up. Head and Face Medicine. 2010;6. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels JSM. Central odontogenic fibroma of mandible: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. sept 2004;98:295‑300. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaoka K, Mogi K, Ishii H. Central fibroma in the ascending ramus of the mandible. Case report. Australian Dental Journal. 1999;44:131‑134. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sepheriadou-Mavropoulou Th, Patrikiou A, Sotiriadou S. Central odontogenic fibroma. International Journal of Oral Surgery. 1985;14:550‑555. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puppala N, Madala JK, Mareddy AR, Dumpala RK. Central odontogenic fibroma of the mandible. Journal of Dentistry for Children. 2016;83:94‑97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehinejad J, Ghazi N, Heravi F, Ghazi E. Concurrent central odontogenic fibroma (WHO type) and odontoma: report of a rare and unusual entity. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, Medicine, and Pathology. nov 2015;27:888‑892. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zia M, Arshad A, Zaheer Z. Central odontogenic fibroma: a case report. Cureus [Internet]. 30 avr 2018 [cité 6 févr 2020]; Available on: https://www.cureus.com/articles/11336-central-odontogenic-fibroma-a-case-report [Google Scholar]

- Pushpanshu K, Kaushik R, Punyani SR, Jasuja V, Raj V, Seshadri A. Concurrent central odontogenic fibroma (WHO Type) and traumatic bone cyst: report of a rare case. Quant Imaging Med Surg. déc 2013;3:341‑346. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney LA, Bradford J, Cohen M, Glickman RS. The aggressive odontogenic fibroma: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:321‑324. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash U, Shapoo MI, Chauhan R. Central odontogenic fibroma: a case report. Journal of advanced medical and dental sciences research. avr 2016; 4. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield IDF. Central odontogenic fibroma: report of case. Journal of Oral Surgery. 1981;39:218‑220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt-Smith SR, Ell-Labban NG, Tinkler SM. Central odontogenic fibroma. International J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1988;17:87‑91. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kaffe I, Buchner A. Radiologic features of central odontogenic fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;78:811–818. [Google Scholar]

- Santoro A, Pannone G, Ramaglia L, Bufo P, Lo Muzio L, Saviano R. Central odontogenic fibroma of the mandible: a case report with diagnostic considerations. Ann Med Surg. 2016;5:14–18. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto I, Gunji A, Omura K. Central odontogenic fibroma of the maxilla. Asian J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;15:288–291. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler HJ, Nersasian RR, Cataldo E, Pochebit S, Dayal Y. Multiple dental follicles with odontogenic fibroma-like changes (WHO type). Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66:78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado H, Mesquita P. Central odontogenic fibroma of the maxilla − a case report. Rev Port Estomatol Med Dent Cir Maxilofac. 2014;55:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schussel JL, Gallottini MHC, Braz-Silva PH. Odontogenic fibroma WHO-type simulating periodontal disease: report of a case. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hara M, Matsuzaki H, Katase N, Yanagi Y, Unetsubo T, Asaumi J-I, et al. Central odontogenic fibroma of the jawbone: 2 case reports describing its imaging features and an analysis of its DCE-MRI findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:e51–e58. [Google Scholar]

- Rebai-Chabchoub N, Marbaix E, Iriarte Ortabe JI, Reychler H. Central odontogenic fibroma. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 1993;94:271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iordanidis S, Poulopoulos A, Epivatianos A, Zouloumis L. Central odontogenic fibroma: report of case with immunohistochemical study. Indian J Dent Res. 2013;24:753–755. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hupp JR, Ellis E, Tucker MR. Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery. St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier 2014. [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Radiological features of the anatomical elements surrounding central odontogenic fibroma.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 PRISMA flowchart of the systematic literature review. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Distribution of central odontogenic fibroma by age and sex. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Distribution of locations of central odontogenic fibroma. (A) According to the involved jaw (maxilla or mandible). (B) According to the site involved within the maxilla or mandible. The sum of the theses percentages is higher than 100% because a lesion can be located in several sites. This figure was made using Servier Medical Art templates − https://smart.servier.com. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Therapeutic approaches used in the treatment of central odontogenic fibroma. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Pedagogical summary of the management of a central odontogenic fibroma. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.